On Friday January 27, 2023,

Amos Eno Gallery hosted a public program during Aaron Wilder's solo exhibition

Omission Rituals that included a dialogue between the artist and art critic

Daniel Larkin. Originally, the discussion was planned to also include artist

Katrina Majkut who had a solo exhibition concurrent with Wilder's in the gallery's project space entitled

Fair Play. However, due to illness, Majkut was unable to attend the program. The following text is an edited transcription of the dialogue between Larkin and Wilder with images of the three artworks discussed.

Image courtesy of Emireth Herrera Valdés

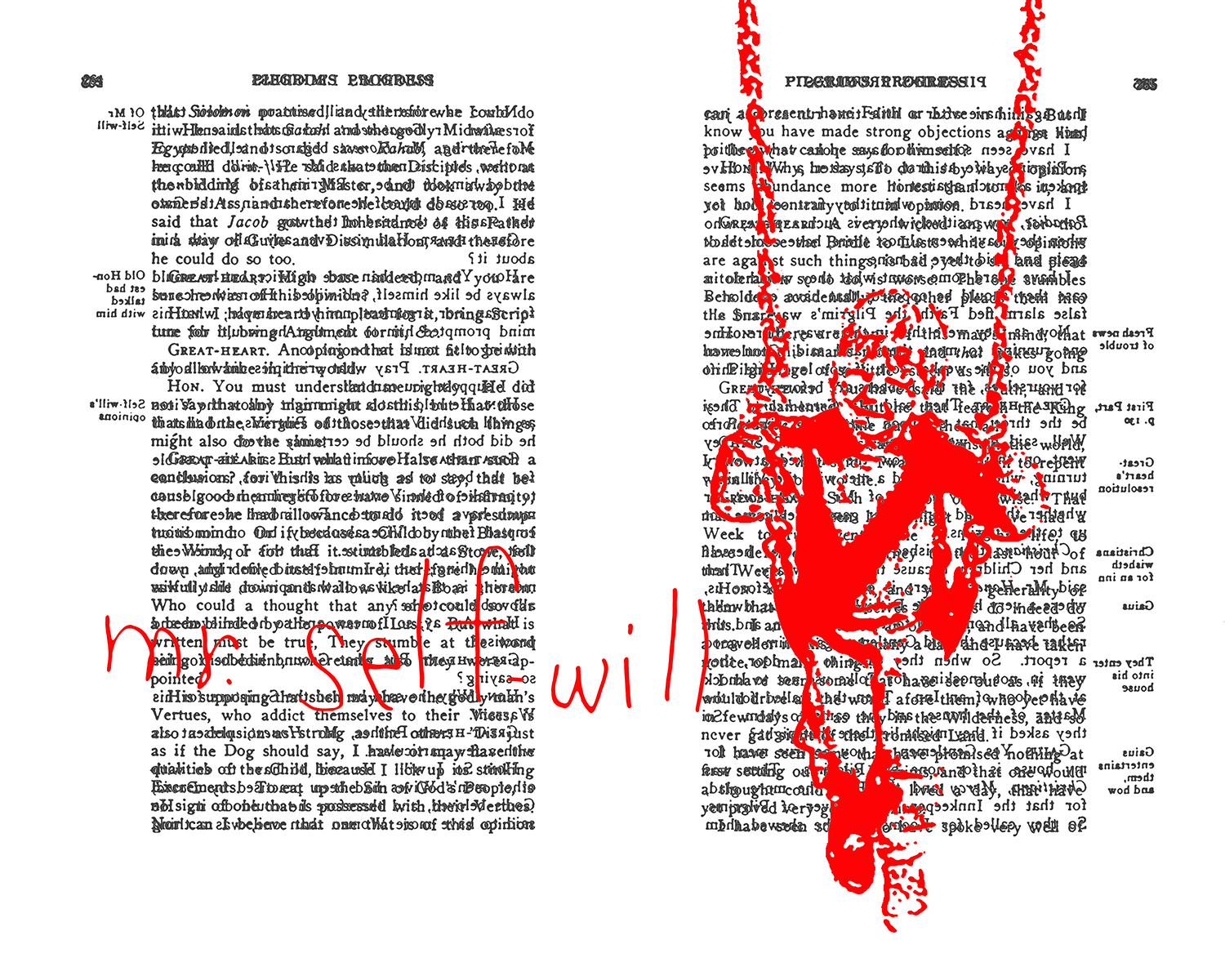

Aaron Wilder,

Season’s Greetings: Threat to Men (Myth, Identity, and Social Interaction, Thompson & Hickey, 1989), 2022, Inkjet Print from Digitally Edited Scan of 120 Film (Shot on a Holga), Academic Text

Daniel Larkin: So Aaron, why did you put a Santa hat on a cactus’ head?

Aaron Wilder: The piece you are asking about is part of my new project

Season's Greetings. I actually didn't put the Santa hat on the cactus. The project began as a critical inquiry into how the holiday is presented publicly. So, I didn't stage any of the photographs in the series. Instead, I photographed Christmas decorations other people decided to publicly display in Phoenix, Arizona (where I grew up), San Francisco, California (where I used to live), and San José, California (where I used to work).

Daniel Larkin: The text is a bit tricky to make out. Can you share a bit about why you decided to create text that was hard to read?

Aaron Wilder: I decided to process my own personal, not-so-positive feelings about the Christmas holiday through two sources: photographing decorations of others I encountered and academic journal articles focusing on the holiday through a range of subjects from economics to sociology and beyond. Initially, I didn’t plan to include the text visually in the work itself, but that changed over the past year. This is a project I’ve been working on for years and I’ll continue working on it in the near future. This series was shot on a Holga film camera mostly made of plastic, known for its distortions and imperfections. I had been using this camera for years on my black and white film photography project

Where is Home? Season’s Greetings is my first project working with color film. My photographic works are almost all a hybrid analog/digital process of scanning film negatives and editing them digitally. I really had no idea what I was getting myself into and very quickly learned that editing color film scans was far more time consuming than black and white. Before I decided to incorporate the text visually in the images, a viewer wouldn’t necessarily know how much time and labor I put into editing. They’d see the imperfections of the Holga with color distortions and blur, but not witness any part of the labor-intensive and time-consuming editing process of removing dust, scratches, etc. The images felt incomplete without references to the texts. But when I incorporated the text on the top layer of the digital image, that also felt incomplete. Then I thought about how the text could serve a bigger role than associations of criticality through these academic journal articles, by also providing a window into the process by making visible some of the imperfections I spent so much time erasing. So, instead of small quotes, I took a whole page from the paired academic article, selectively emphasized some statements by erasing others, and inserted that incomplete text between the unedited background image and the layer with all the edits to remove imperfections, which then made visible some of these edits shown as gaps in the text. To me, the fragmented text also has a metaphorical role of the incompleteness of memory and our selective (un)awareness of associations between the Christmas holiday and broader aspects of economic, psychological, and sociological forces.

Daniel Larkin: Could you read this text to us?

Aaron Wilder: Sure. There are four text fragments. The first is "rational, analytical, assertive, and self-sufficient." The second is "threat to men." The third is "To men, santa is a distraction, or worse, an obstacle in their paths—hence, he is someone to be avoided. When alone, males from about age 20 to 60 not only avoided interaction with Santa, they refused to even acknowledge his existence." And the fourth is "interacting with Santa at the mall falls outside what most men consider appropriate for their social identity."

Daniel Larkin: Why is Santa Claus identified as a distraction or an obstacle?

Aaron Wilder: Gender is one of the many lenses through which I am viewing, analyzing, and critically engaging with the Christmas holiday in this project. The text from the academic article not fully erased underscores a concept that resonated with me not only about the holiday broadly, but also this specific image depicting someone’s decision to place a Santa hat on this very phallic cactus.

Daniel Larkin: In the title of this work, Santa Claus is singled out as a threat to men. How do you understand this threat? Is there anything else you want to share about this title?

Aaron Wilder: While visibly altered and conceptually re-contextualized sufficiently enough to not be a violation of copyright, I felt it important to at least reference the academic article in the title of my own artwork. The title is a nod to the original source of the text:

Myth, Identity, and Social Interaction: Encountering Santa Claus at the Mall by William E. Thompson and Joseph V. Hickey, published in the journal Qualitative Sociology in 1989. Therefore, I am concurring with Thompson and Hickey in their research on men feeling threatened by shopping mall Santas.

Aaron Wilder,

Delivered Under the Similitude of a Dream: You seemed to sail through our family breakup unscathed (as long as you had plenty of toys to play with), 2017, Inkjet Print from Digital Mixed Media

Daniel Larkin: So Aaron, there are a lot of layers to this piece. Could you start by telling us about the text (which is hard to make out)?

Aaron Wilder:

Delivered Under the Similitude of a Dream is a project that revolves around deconstructed pages from John Bunyan’s 1678 book

Pilgrim’s Progress, a heavily didactic tale of how to live your life as a Christian. This project began as an evolving, immersive installation during my MFA studies at the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI). At this same time, my family had recently sold the home I grew up in, which resulted in a need to amass, move, and review materials from my childhood. Also around this same time, I found a copy of the book

Pilgrim’s Progress in the “free” bin at the SFAI library. Since this was one of the first books I remember reading as a child, the simultaneity of re-discovering this book at a time of re-visiting my childhood memories resulted in this explorative experiment. I installed the immersive installation in one of the brick vaults of the San Francisco Mint in 2017. I completely covered the walls of this vault with overlapping, ripped out pages from different versions of

Pilgrim’s Progress. I then projected onto the wall-mounted pages the 75 edited images of myself throughout childhood juxtaposed to the names of 75 characters from Bunyan’s book. After the installation at the Mint, I created a series of 75 digital mixed media collages pairing the imagery of the installation projections with overlapping scanned texts from the version of

Pilgrim’s Progress I found at the SFAI library. Each collage is essentially an individual spread of 2 pages front and back as if the paper were invisible and only the text from the double-sided pages is visible, making it difficult to read much of what each page actually says.

Daniel Larkin: Who is the boy in the swing? Can you tell us a little bit about the original context of this image?

Aaron Wilder: That’s a photo of me as a child. I don’t remember specifically who took the photo or the site of this swing. In this project names of characters from Bunyan’s book are applied to images of me as a child in non-chronological order. In doing so, I apply the guise of 75 characters from Bunyan’s book to myself at different points throughout childhood. This excerpt is slightly less than half of the full series of 75 collages.

Daniel Larkin: Was there a particular reason why you chose the color red?

Aaron Wilder: This is partially due to a subconscious attraction to the black/red/white color scheme which can be associated with normative socializing, white-washed children’s literature from my parents’ generation like

Fun with Dick and Jane and simultaneously associated with possible aesthetics of a ransom note. There’s also a slight stereoscopic effect of the flat red on top of the flat black letters creating a tiny illusion of depth drawing attention to the different layers (both aesthetically and conceptually).

Daniel Larkin: Why did you decide to juxtapose this particular image of you as a boy on a swing with the term

Mr. Self-Will?

Aaron Wilder: Mr. Self-Will is a minor character in Bunyan’s book and says nothing himself. Instead, he is someone talked about by the characters Mr. Great-Heart and Mr. Honest. Without Mr. Self-Will speaking himself, the other two determine him to be an example of a bad Christian. About him Mr. Honest says “He held that a man might follow the Vices as well as the Virtues of the Pilgrims, and that if he did both he should certainly be saved.” A child on a swing can serve as a metaphor on this kind of pendulum path between vice and virtue. If a child is old enough, they can propel themself in either direction. If the child is too young to have legs that reach the ground, someone older would be the one to propel the child in one direction that also ultimately swings the child in the opposite direction. Perspective and voice also are key factors in who has the authority to tell the story and define what is a vice vs. what is a virtue.

Daniel Larkin: The title for this work is

Delivered Under the Similitude of a Dream: You seemed to sail through our family breakup unscathed (as long as you had plenty of toys to play with). Could you share a bit about what you are trying to invoke with this title?

Aaron Wilder: In this project I explore the concept of layered authorship. Feelings of nostalgia for a lost childhood are uncomfortably juxtaposed to a rejection of prescribed life trajectories based on religion, morality, and other factors of social construction. The title of each collage stems from the audio paired to the image projections from the original installation at the San Francisco Mint. The audio was a recording of my own voice reading this statement and then lowering the pitch so it sounds like a menacing call to collect ransom. Each audio fragment became a collage subtitle and is a statement from cards and letters sent to me from who I’ll refer to as a Christian authority figure in my life since childhood. With this particular collage of Mr. Self-Will and the image of me on the swing, I am trying to evoke the complexity of how a child tries to make sense of these fragmented literary and interpersonal messages without being able to fully comprehend the impact of coercive evangelism.

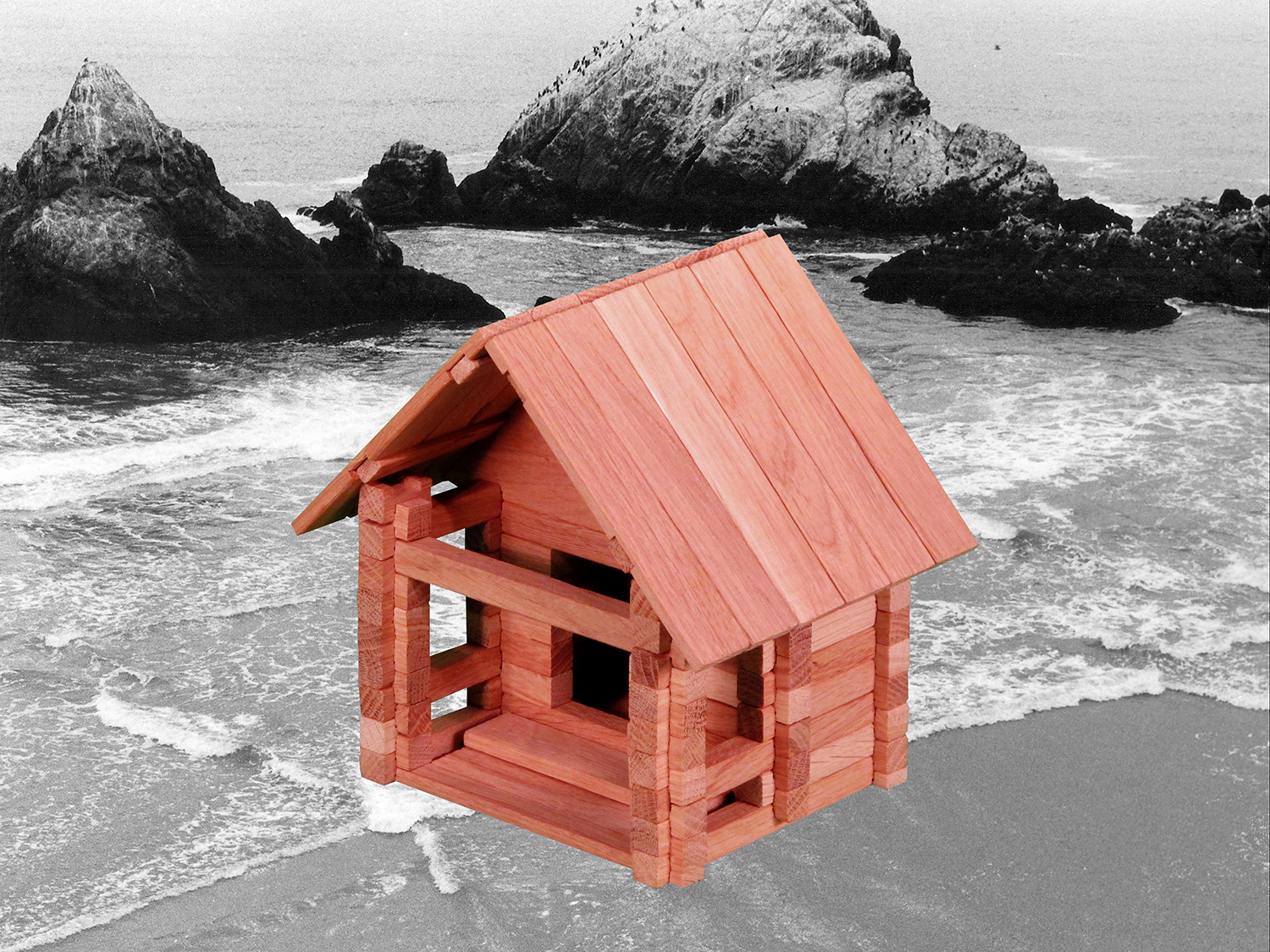

Aaron Wilder,

Neither Sand nor Rock, 2022, Inkjet Print from Digital Photography Collage

Daniel Larkin: So Aaron, as we approach this third work, can you tell us first a bit about the landscape? Does it have any particular meanings?

Aaron Wilder: Most of my projects, particularly those involving aspects of photography, mix elements of analog and digital processes together. In

Neither Sand nor Rock, color digital photographs of children’s building block toys in various stages of (in)completeness are super-imposed onto black and white 35mm film photograph backgrounds. These analog background photographs are images recycled from several earlier projects. This particular background photograph is of Land’s End, the northwest coast of the San Francisco peninsula, and was a part of my 2015-2016 black and white 35mm film photographic project

West Bay. All of the background images in

Neither Sand nor Rock were taken either in San Francisco or California’s Central Valley while I lived in San Francisco 2015-2020.

Daniel Larkin: When we met a few weeks ago, you mentioned that this log cabin has some particular connections with your father’s story? Could you share a bit about that with us?

Aaron Wilder: I wouldn’t necessarily say this image is directly connected with my father’s story, per se. This specific image is more of a piece of my processing of my father’s priorities as I perceive them enacted upon me starting in childhood. At its core,

Neither Sand nor Rock is an attempt to understand the child as a battleground between opposing parental forces exerted on them. What’s displayed here is an excerpt of a larger project I’ve been working on since 2016. There are two sets of toy building blocks: one is more cabin-looking superimposed onto more rustic or rural backgrounds (sequences I refer to as

Daddy’s House) and the other is more urban- or suburban-looking superimposed onto more metropolitan-looking backgrounds or spaces flagged for suburban development or actively being transformed into city housing (sequences I refer to as

Mommy’s House).

Daniel Larkin: Now it’s technically impossible for a log cabin to float on water like this. Why did you feel drawn to overlay the log cabin onto waves as you did?

Aaron Wilder: All of the juxtapositions between foreground and background in

Neither Sand nor Rock are technically impossible, but this specific work with its waves is one of the ones even harder to envision in reality. The range of (un)believability in these juxtapositions of houses on background landscapes is an integral component of this project. The contrast of digital color and analog black and white adds a further layer of complexity onto the other conceptual juxtapositions between mother/father and urban/rural dichotomies. I’ll share a quote from Sarah Bernhardt, Executive Director of

Intersect Arts Center in St. Louis, Missouri. She wrote the following about this project in the catalog for the May-September 2021 group exhibition

Ritual: "

Neither Sand nor Rock takes its name from the Christian children’s Sunday School song

The wise man built his house upon a rock. The song is a retelling of a parable from the Bible that details a wise man building his house upon a rock foundation while a foolish one builds his on sand. In ensuing bad weather, the house on the sand is washed away while the one on rock stands firm. The story acts as a metaphor to caution and encourage readers to build their life upon the solid “rock” of faith in God and not to be swept away by the insecurities of building life on the follies of secular culture. Wilder has created this ongoing series of photographic collages as a meditation on the psychological, imaginative, and physical gaps between childhood and adulthood. Children create elaborate rituals through play, many of them microcosms of the rituals they are exposed to by their parents and broader cultural norms. As we consider the many rituals that create a sense of home, these images help us reflect on the incongruity of our childhood imagination of the ideal home, and the harsh, sometimes seemingly bleak and inhospitable reality of our adult surroundings. The bright, seemingly hyper-solid blocks in various states of construction and deconstruction occupy a representation of either

Mommy’s House or

Daddy’s House for Wilder. The architectural forms float with a reimagined sense of gravity leaving us feeling a bit insecure and ungrounded. These jarring composite photographs illuminate the stark gap that can occur when the rituals of childhood are disrupted, transition, or clash with belief systems in adulthood and they ask what sorts of new construction, new environments, and new foundations might be more hospitable.”

Daniel Larkin: When I engaged with this work during opening weekend, I kept coming back to the ideas of projection and transference: the way that we can project something that belongs to our father into a landscape or an environment in which he was not actually there. Is that something you’ve thought about?

Aaron Wilder: Daniel, I appreciate your connection of this work to those ideas, but I feel you are far more eloquent than I in making those connections. The one thing I will say is that, in a way, this project explores the effects of projection and transference onto me and that is visualized through my projection and transference of my parents’ subconsciously expressed priorities as housing fragments onto these landscapes. The one thing I will say is that, in a way,

Neither Sand nor Rock explores the effects of projection and transference onto me and that is visualized through my projection and transference of my parents’ subconsciously expressed priorities as housing fragments onto these landscapes.