by Aaron Wilder, Curator of Collections and Exhibitions at the Roswell Museum

Roswell Daily Record

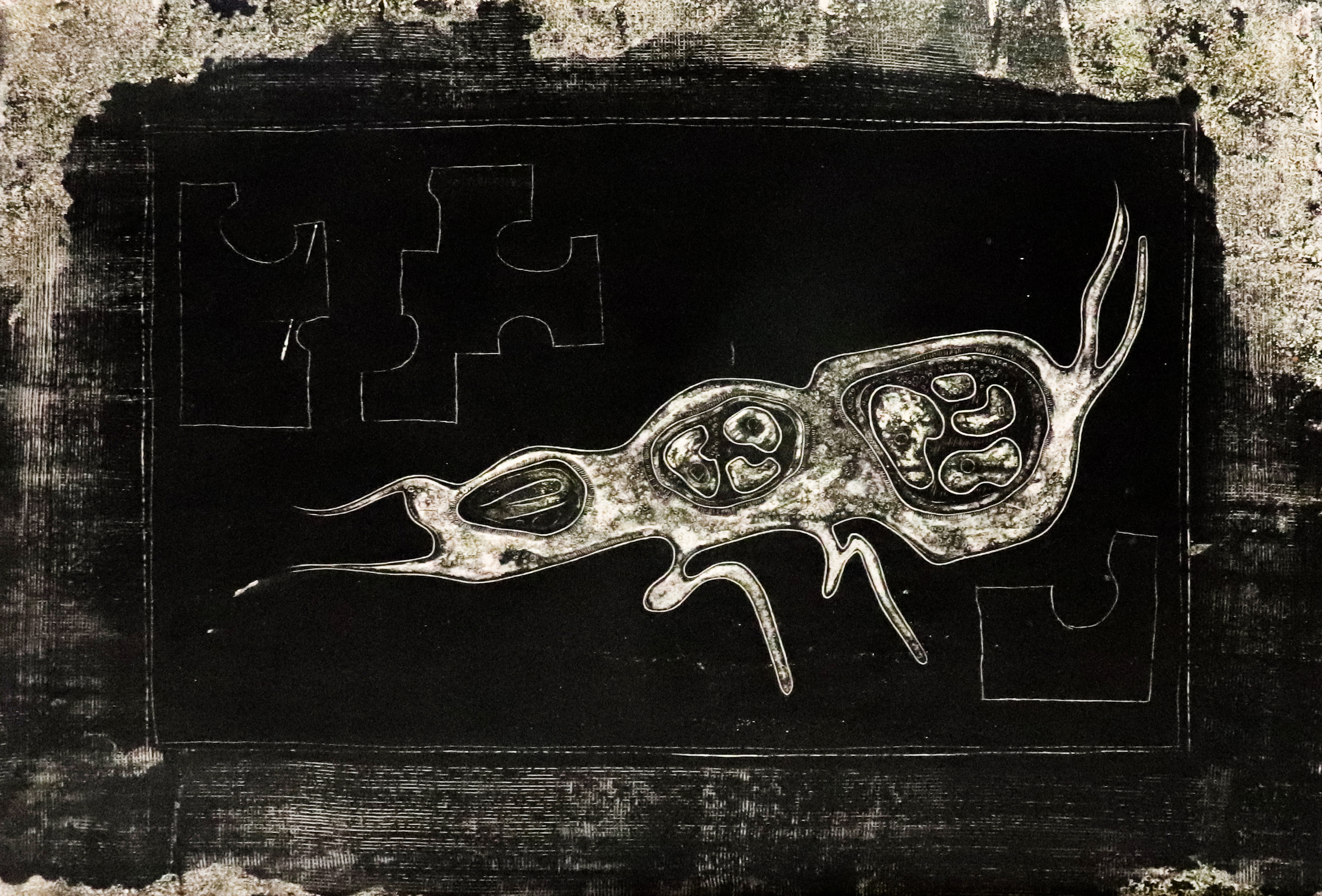

“Larvaeic” by Cady Wells, 1946, Ink, Watercolor on Paper, Acquisitions Fund Purchase, 1982.030.0001

For the catalogue of his first New York exhibition, Georgia O’Keeffe wrote of her friend and fellow artist Cady Wells: “I am glad you are showing Cady’s paintings… because I think we are the two best painters working in our part of the country.” Her comment reflects both the mutual respect between the two artists and the significance of Wells’s work in the modernist history of the American Southwest.

Henry Cady Wells was born in 1904 into a first-generation wealthy Massachusetts family who had founded the American Optical Company in Southbridge. He was educated at a series of private schools, five of which he left before completing, likely in part because of his struggle with his inner homosexual identity. In the mid-1920s, Wells’s father sent him to the Evans School near Tucson, Arizona, hoping that life in the rugged terrain of the Southwest might make his son more masculine. As writer Meg Selig noted in a 2022 Denver Art Museum blog post, “A fiercely private person, Wells never openly acknowledged his homosexuality. However, reading through the archived letters sent between Wells and his family and friends, scholars have come to realize that those close to Wells were aware of his sexuality, while willing to keep his secret.”

In 1932, Wells spent time in Bali, China, and Japan. While in Japan, he became interested in traditional brush painting and began a serious study of the technique. Later that year, traveling through New Mexico on his way home to the East Coast, Wells met E. Boyd, with whom he shared an appreciation for Spanish Colonial art. About artist havens like Santa Fe, Christian Waguespack wrote in El Palacio Magazine in 2017 that “these meccas for artists, writers, and often offbeat characters presented a freedom still unavailable to folks back East, where the stodgy holdovers of Victorian morality could seem oppressive. Art and life were inexorably linked for Wells, and the ability to express his sexual orientation went hand in hand with a freedom in exploring unconventional directions in his art. In New Mexico, Wells surrounded himself with a community that allowed him to more fully embrace his queer identity, all the while pursuing a distinctive view of the Southwest in his artwork.”

Predominantly a self-taught artist, Wells began painting seriously in the summer of 1933, when he enlisted Andrew Dasburg as a teacher. Dasburg introduced him to watercolor, a medium that became central to his work. That same year, Wells wrote to New York gallerist Alfred Stieglitz: “I am 28 years old and have spent most of my life so far trying to justify my existence to my family—and not to myself—which wasn’t smart. But this summer for the first time I forgot that completely and found myself doing something I loved… I know that everything is going to be alright because I can paint because I can’t help it.”

Also in 1933, Wells had his first exhibition at what is now the New Mexico Museum of Art, showing with fellow artists Agnes Pelton and Raymond Jonson. He later reflected, “The creative process in painting is based on my needs and wishes to share with others what I cannot share in any other form.” In 1935, Wells returned to Japan for an additional two months of study in the ink brush technique. When he came back to the United States, he purchased a hacienda on ten acres in Jacona, north of Santa Fe.

In the 2011 book “Light, Landscape and the Creative Quest: Early Artists of Santa Fe,” Stacia Lewandowski wrote, “After the outbreak of World War II, Wells enlisted in the US Army. As a sergeant, he was first stationed in England and later France and Belgium. Concerned about the destruction of irreplaceable historical and religious objects, Wells spent part of his wartime activities confiscating and hiding significant objects out of harm’s way. (After the war he notified officials of their locations.) During the final nine months of the war, Wells witnessed harrowing scenes of destruction while producing aerial topographical maps of Germany. He was greatly affected. These wartime experiences remained with Wells long after he returned home. In New Mexico, he found it difficult to work at his beloved hacienda. It troubled him to live there; his property was situated uncomfortably close to Los Alamos. The government facility continued to work on weapons creation, which the artist found abhorrent.”

According to biographer Lois Rudnick, Wells’s postwar paintings “responded to the angst of the Atomic Age with references to barbed wire and the transformation of landforms into weapons, while others suggested prehistoric creatures.” His technique became increasingly complex. For these later works, he often used gouache to create deep black surfaces that he then textured and tinted using brushes of only a few hairs, along with palette knives, dental tools, and even dog combs for incising. This series of paintings, made between 1946 and 1948, earned Wells his greatest critical acclaim. His painting “Larvaeic” in the Roswell Museum’s collection was made during this period and depicts what appears to be a creature mutated by exposure to radioactive materials.

In a 1946 letter to his friend Merle Armitage, Wells wrote: “I had an argument with a couple of grim painters the other day about isolating oneself from the horror of world events so they wouldn’t affect one’s creative ability. Nothing could be further from the way I feel and told them that to be excitingly creative now meant being aware and part of the stream of events—that one’s work had to be part of everything that was happening—evil as it was.”

Wells was an active participant in the New Mexico art community. He was a member of the Rio Grande Painters group, served on the board of directors of the School for Advanced Research in Santa Fe, and helped found the Jonson Gallery at the University of New Mexico. He was also an avid collector. Wells acquired a collection of about 200 santos, traditional wood carvings of saints, which he donated in the early 1950s to the Museum of International Folk Art and the Museum of Spanish Colonial Art. These donations formed key components of both institutions’ collections and demonstrated his commitment to preserving New Mexico’s distinct artistic traditions. Cady Wells died of heart failure in 1954 at the age of 49.

The statement “It’s Your Art” is meant to emphasize that the Roswell Museum’s collection is your collection. Despite the museum’s closure due to the October 2024 flood, staff continue to work behind the scenes on care for and conservation of collection objects. Please stay tuned for more from the Roswell Museum. We appreciate the outpouring of support from the community during our closure. And remember, “It’s Your Art.”