by Aaron Wilder, Curator of Collections and Exhibitions at the Roswell Museum

© Roswell Daily Record

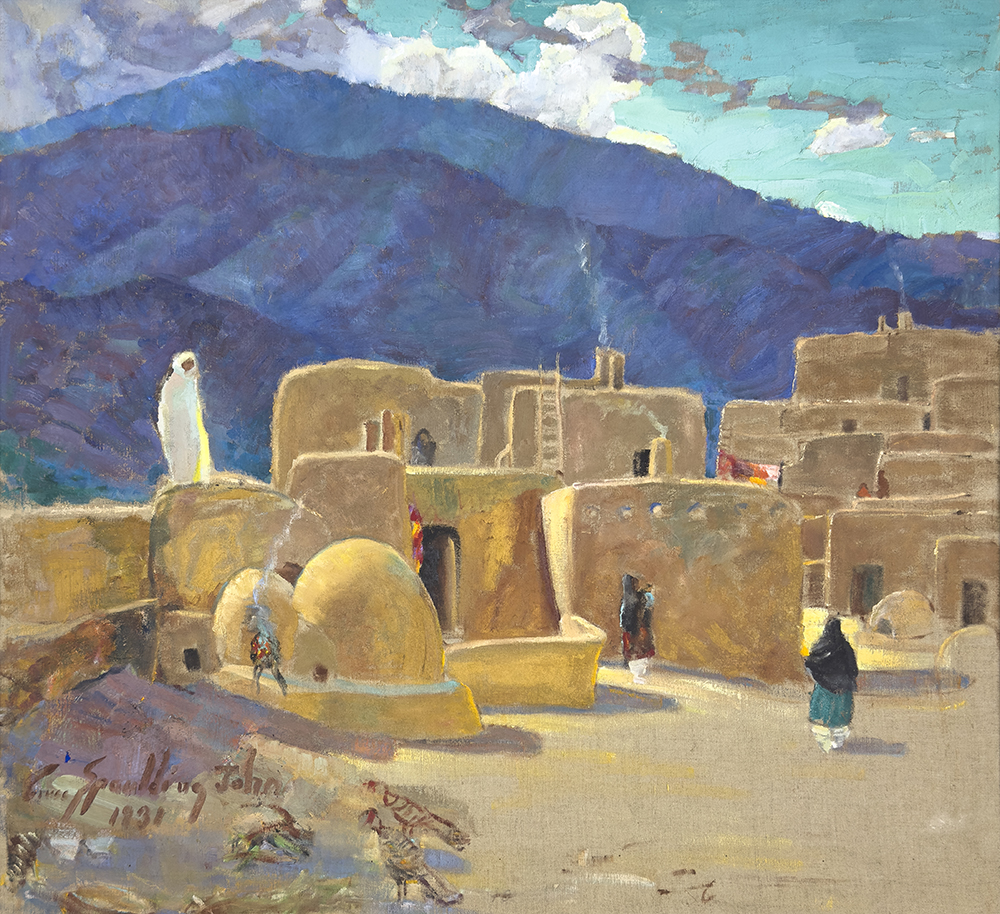

“The Lone Sentinel” by Grace Spaulding John, 1931, oil on linen. Gift of Patricia John Keightley, Roswell Museum collection.

Last month, the Roswell Museum column focused on the painting entitled Chimera by Sue Hettmansperger. The column’s new name is “It’s Your Art” to emphasize that the Roswell Museum’s collection is your collection. Despite the museum’s closure due to the devastating October 2024 flood, staff continue to work behind the scenes on the care and restoration of collection objects.

This month, I am focusing on artist Grace Spaulding John, who was born in Battle Creek, Michigan, in 1890. In the 2024 book “Making the Unknown Known: Women in Early Texas Art, 1860s-1960s,” Eleanor Barton wrote that her father Helim “was a newspaper editor and publisher, and her mother, Gertrude, was a talented pianist ... newspaper assignments enabled the family to travel to various parts of the country, and young Grace spent time in Tennessee, Vermont, New York, and New Orleans before settling in Beaumont, Texas, in 1903.”

Ten years later, John married Roy Keehnel, with whom she had two children, Jean and Patricia. With the couple disagreeing on John’s time spent on art vs. domestic duties, it wasn’t destined to last long. In a statement for the exhibition Never a Dull Moment: The Art of Grace Spaulding John at the Rosenberg Library Museum, an unidentified author wrote, “When the marriage ended in 1917, John moved to New York to study at the National Academy of Design and the Art Students League.” Then, in 1921, the artist moved to Houston, Texas and married Alfred Morgan John, who was more supportive of his new wife’s artistic ambitions.

Sitting in front of her subject, typically out in the elements, John might create a preliminary sketch before starting to paint then and there. This method of painting is referred to as “plein air” from the French term “in the open air” and the European Impressionists, such as Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, were its main proponents. Barton explained how the artist adapted to this practice by saying, “John was believed to be the first woman in Houston to wear ‘trousers.’ Because she painted outdoors and had to carry her own art supplies, John had adopted a practical uniform consisting of a long tunic over loose-fitting pants. A radical departure from typical women’s attire of the day, the ensemble allowed her to better navigate the natural terrain.”

A unique aspect of her work was John’s use of brown linen as the surface on which she’d paint, and she’d first coat it with rabbit skin glue. This is a fairly labor-intensive process that yields the benefits of a tighter surface and a protective barrier against oil paint penetration. Barton further elaborated on the artist’s approach to painting by saying, “John often left sections of the canvas unpainted, allowing the natural linen to show through. This technique produced a dramatic effect and was viewed favorably by art critics in various published reviews.” Inspired by the style of Vincent Van Gogh, John’s aesthetics were both dreamlike and lucid. Barton explained, “Using thick, short brushstrokes and a vibrant palette, John’s paintings were dramatic and bold. She rarely used dark colors and applied contrasting shades side by side without blending the paints together.”

The 1920s would prove to be a pivotal time in John’s artistic career. She was one of only eight artists to receive a prestigious fellowship to study at Louis Comfort Tiffany’s Laurelton Hall in New York in 1923. A few years later, she embarked upon trips abroad that significantly impacted her practice as an artist. In 1927 she went to multiple European countries, and in 1928 she went to Mexico. During her travels, John had produced enough paintings for a solo exhibition and, indeed, she got one. John was one of the first artists invited to have a one-person show at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston. Barton further explained John’s success in the 1920s by saying, “She had more commissions than she could handle, noting she had learned that in order to make her work profitable, she had to make her work marketable… she recognized the need to be a talented businessperson in addition to being a talented artist… When she sought media coverage for her artwork, she would type up her own article and submit it to the paper along with her own photographs. This saved the paper the time and expense of sending out its own reporter and photographer, and as a result, she received frequent publicity for her work.”

Another impact of international travels on John was the mutual support of artists. She organized Houston’s very first artist collective gallery in 1930. Barton wrote, “In Mexico City she observed artists from Mexico, North America, and Europe working together in an organized way to promote and sell their work. Upon her return to Houston, she shared her experiences with some of her fellow artists, and the idea behind the Houston Artists Gallery was born. The majority of the twenty-two founding members of the Houston Artists Gallery were women… The gallery was staffed by volunteer artists who not only sold artworks but also sponsored auctions and lectures. Houston Artists Gallery was not the only art gallery in the city, but it was distinctive from the others. As a rule, only member artists could show their work, and all of the art was made in Houston.”

John made her first trip to New Mexico in 1931. She studied in Taos with Emil Bisttram, and the regional colors and subject matter can be seen in her painting in the Roswell Museum’s collection. Entitled The Lone Sentinel, the painting depicts adobe structures, most likely the Taos Pueblo, against a mountainous backdrop. A sentinel is someone who guards something. Clad in all white and standing atop one of the adobe structures on the left side of the painting, John has identified this individual as the one with the sole responsibility of guarding the village or pueblo. This painting was given to the Roswell museum in 1995 by the artist’s daughter, Patricia John Keightley.

John again went to Mexico in 1934. After the death of her beloved husband in 1936, Barton explained the artist’s ensuing restlessness by saying, “Seeking a more vibrant art scene that would afford her more opportunities, Grace left Houston, living for months at a time in California, New York, or Mexico… She spent the summer of 1937 in Santa Fe… Despite the growing popularity of modern art in America, John continued to paint in her signature impressionist style… ‘My art stems from the impressionistic school. Naturally, it has a lingering touch of that style. And the fact that I haven’t gone modern doesn’t worry me one bit.’” Impressionism was indeed one of the many modern art movements and based on the timing of when John was creating her art, it was certainly modern art. So, what did she mean when she said she hasn’t “gone modern?” Given the growing popularity of abstract art at the time of this quote, John likely was contrasting her more representational, or “realistic,” style against the increasingly abstract art trends. John passed away in 1972 in Houston.

Please stay tuned for more from the Roswell Museum. We appreciate the outpouring of support from the community during our closure. And remember, “It’s Your Art.”