Amos Eno Gallery

proudly presents

Unstable Language

A Group Show Featuring Artwork by 19 Artists, Curated by Aaron Wilder

October 20-December 1, 2025

Online exhibition on Artsy.net

Press Release:

Curated by Aaron Wilder, Unstable Language is an online-only exhibition hosted by Amos Eno Gallery on Artsy.net from October 20 to December 1, 2025. This exhibition invited artists to reflect on art’s power for change and resisting harmful narratives.

Our understanding of the world around us is based on language, the filter through which we understand ourselves and others. Our understanding can be skewed by governmental, media, and other institutional actors through efforts to redefine terms to forward a biased agenda, censoring or distorting facts, and framing perception through propaganda. The ultimate goal of these institutions is to engineer our behavior so that we act in ways compliant to and complicit in the perpetuation of systems of dominance and control.

Saying or doing something that challenges the status quo has the potential of altering what can be thought of as acceptable. This is why societal norms are fortified by powerful systems, including threats of shaming, prosecuting, and abusing anyone who seeks to rock the boat. Paralysis from how overwhelmingly intricate and pervasive the system can seem is the intended effect. One doesn’t have to fully understand or take on the entirety of the system. Waiting for the ideal theory, leader, or revolution only benefits institutions of power and their continued domination of us.

Art, as a kind of language, has the power to reinterpret and rearticulate relationships between the individual and established norms, providing a substantial opportunity to resist institutions of power and the dominant narratives they shout. Just as art enables new ways of seeing, it amplifies our voices. Art provides the platform to put us on a level playing field so that we can shout back louder. Art, as an unstable language, is powerful because it is full of potential for challenging harmful dominant narratives. If we can see ourselves as capable of enacting change, we can use our voices to disrupt today’s system. We face a future full of possibilities. It’s time to speak and to act.

Unstable Language showcases how artists use their work to speak and act against oppressive narratives and reclaim reality. Participating artists are Tyler Alpern, Sandra Cavanagh, Lulu Luyao Chang, Charles Compo, Isabella Covert, Annika Fricke, Ann Guiliani, James Hannaham, Scott David Isenbarger, Cecil W Lee, Nasrah Omar, Kasia Ozga, Sean Riley, Jean Seestadt, Christopher Squier, Clark Stoeckley, Chanya Vitayakul, Emma Werowinski, and KR Windsor.

Founded in 1974, Amos Eno Gallery is one of New York City’s longest operating artist-run gallery spaces. The gallery is a nonprofit organization providing a full season of exhibits by emerging and mid-career artists working in visual, performance, installation, interactive, and/or digital media/video. Amos Eno serves as an alternative platform for professional artists in a variety of media, giving precedence to artistic expression freed from commercial restraints. By presenting a rich schedule of exhibits and participatory events, we help promote the cultural growth of our community.

Curatorial Essay:

Our understanding of the world around us is based on language. Our thinking is essentially talking to ourselves. Language is the filter through which we understand ourselves and others. That filter is influenced constantly by an extensive array of forces, resulting in manipulated inferences. Canadian-American linguist Samuel Ichiye Hayakawa defined an inference as “a statement about the unknown made on the basis of the known.” These are connections we make through logic to move between ideas where we come to a conclusion based on available information. This available information is usually skewed by governmental, media, and other institutional actors by redefining terms to forward a biased agenda, censoring or distorting facts, and framing perception through propaganda. The exhibition Unstable Language showcases how artists use their work to speak and act against oppressive narratives and reclaim reality. Participating artists are Tyler Alpern, Sandra Cavanagh, Lulu Luyao Chang, Charles Compo, Isabella Covert, Annika Fricke, Ann Guiliani, James Hannaham, Scott David Isenbarger, Cecil W Lee, Nasrah Omar, Kasia Ozga, Sean Riley, Jean Seestadt, Christopher Squier, Clark Stoeckley, Chanya Vitayakul, Emma Werowinski, and KR Windsor.

Charles Compo, Now That’s What I Call a Target-Rich Environment, 2024, Oil on Canvas, Courtesy of the Artist

Charles Compo slows down the auto-filtering of our contemporary media onslaught through his paintings. He critiques the predefined narratives fed to us by using symbols and visual layering to make hatred and subjugation more identifiable for what they are. “Through the use of symbols,” Compo says, “I engage with painting as a manifestation and manipulation of the visual language of daily life.” His painting Now That’s What I Call a Target-Rich Environment, is loaded with symbolism portraying the visual chaos constantly bombarding us. Part of the title, “target-rich environment,” is itself a euphemism that the corporate world has appropriated (to indicate a field from which can be extracted many profit opportunities) from military terminology (to indicate a battlefield teeming with enemies to attack). In this painting, Compo exposes the insidious nature of language that simultaneously connects and glorifies violence and capitalism. One can see a clear link between mass violence and the gun industry. “Shedding light onto methods of domination and control by reweaving symbolic vocabulary and associations is vital to my reconciliation with the world,” he says. In what Compo describes as “the collective hallucination known as reality,” the deception of everyday language is deconstructed so that we can identify true intent of media to which we’re exposed.

One very effective tool to manipulate using thought is doublespeak, which linguist William Lutz defined as “language that pretends to communicate but really doesn’t. It is language that makes the bad seem good, the unpleasant appear attractive or at least tolerable. Doublespeak is language that avoids or shifts responsibility, language that is at variance with its real or purported meaning. It is language that conceals or prevents thought; rather than extending thought, doublespeak limits it.” To recognize doublespeak, one must question who is speaking, what is being said, to whom the communication is directed, what the circumstances of communication are, the intent, and the impact. Lutz identified four kinds of doublespeak: Euphemism (using positive terms when referring to something negative), Gobbledygook (overwhelming an audience with lots of big words and long sentences), Inflation (making something unimpressive seem impressive or something simple seem complex), and Jargon (using specialized terminology with an audience that doesn’t understand it).

If doublespeak seems vaguely familiar to one or two concepts from a novel you read in high school, that’s because it is. Lutz wrote, “In the nightmare world of his novel, 1984, [George] Orwell depicted a society where language was one of the most important tools of the totalitarian state. Newspeak, the official state language in the world of 1984, was designed not to extend but to diminish the range of human thought, to make only ‘correct’ thought possible and all other modes of thought impossible. It was, in short, a language designed to create a reality that the state wanted. Newspeak had another important function in Orwell’s world of 1984. It provided the means of expression for doublethink, the mental process that allows you to hold two opposing ideas in your mind at the same time and believe in both of them. The classic example in Orwell’s novel is the slogan, ‘War Is Peace.’” Even for those existing outside totalitarian societies, doublespeak is still used constantly and consistently to shape perception, reinforcing dominant narratives.

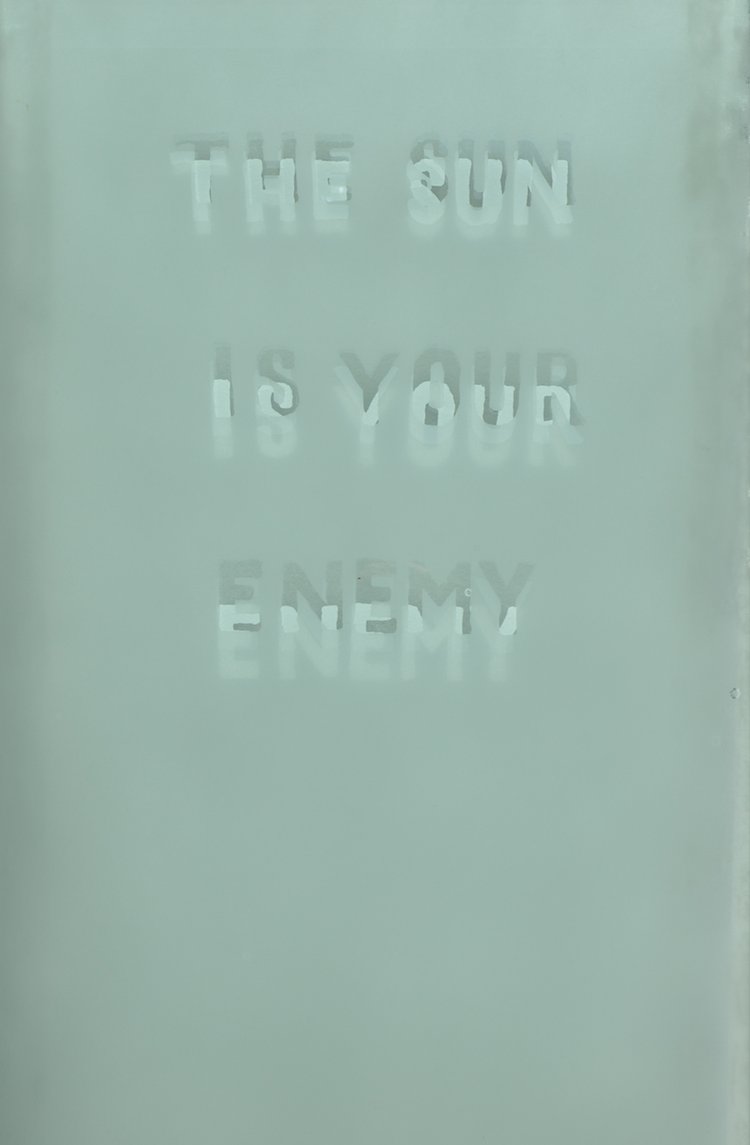

Christopher Squier, Monstratsiya Archive (The Sun Is Your Enemy), 2018, Translucent Spray Paint on Reclaimed Glass, Courtesy of the Artist

Christopher Squier creates art that challenges the attempts to diminish human thought by playing with the role of light, both literally and conceptually. Monstratsiya Archive (The Sun Is Your Enemy) is a sheet of glass on which a seemingly ominous warning about your relationship with our nearest star is inscribed. “The name ‘monstratsiya,’ a variation on the word for ‘demonstration’ in Russian,” the artist explains, “describes a protest movement that began in Novosibirsk and was known for its use of absurdist protest signs and nonsensical chants. Organized annually throughout the 2010s by performance artist Artyom Loskutov, the May Day parade became a celebration of absurdism, using satire, gibberish, and wordplay to reflect on the protestors’ political reality and the possibility of radical speech-acts in the public realm.” In the solid, yet fragile form of glass, Squier gives permanent physical and archival form to these transitory statements. The phrase “the sun is your enemy” can be interpreted in many ways. As a statement imposed on you, it can be an encouragement to resist change or distrust truth for the ultimate perpetuation of the status quo. The artist has said he has placed the protest signs “within a history of political aesthetic acts” to consider “how illegibility and in/visibility might, in certain cases, be rendered as effective as direct action.”

Emma Werowinski, It is what it is, 2025, Assorted fabric, thread, Courtesy of the Artist

Emma Werowinski is a textile artist who uses information as design to assist others to renegotiate their relationships to power. She often positions herself as a translator, making understandable the doublespeak of governments, corporations, and other hegemonic entities. “My goal is to prompt new ways to think critically about the structures around us and work towards future bureaucratic structures that support all people,” Werowinski says. Through design, she presents information more comprehensibly, legibly, and visually. In her exhibited work, Werowinski subtly interrogates the effect of inherited proverbs (short, traditional sayings used to convey a supposed “universal truth”) and how they limit our worldview. “In English,” she says “we have many proverbs that reinforce a narrative that people can’t change. We often turn to them when we don’t know what else to say. Think about how the proverb ‘it is what it is’ can function as the end of a conversation. It makes us passive bystanders in the world, instead of active participants. Instead of selling ourselves short, these works ask what new proverbs can we write to inspire growth and change?” In changing “it is what it is” to “it is what we make it,” Werowinski shows us the simplicity in pausing to think critically about repeated, inherited proverbs to liberate ourselves from limited thinking.

The ultimate goal of a perception shaped by doublespeak is to engineer our behavior so that we, both as individuals and groups, act in ways compliant to and complicit in the perpetuation of systems of dominance and control. For example, in the United States, these systems include the free markets of capitalism, the colonial and imperial implications of American citizens valued above all others, and the notion of “justice” that presumes guilt for those pushed to the margins (people of color, the unhoused, LGBTQ+ individuals, etc.). French social theorist Michel Foucault wrote that “Discipline increases the forces of the body (in economic terms of utility) and diminishes these same forces (in political terms of obedience).” Our capacity to think critically and challenge dominant systems lies in the intentional expression of our abilities to speak and to act. Art can be a productively destabilizing approach to politics. Philosopher Jacques Rancière said “Politics revolves around what is seen and what can be said about it, around who has the ability to see and the talent to speak, around the properties of spaces and the possibilities of time.”![]()

Ann Guiliani, Icon 1 Litigare, 2024, Lithograph, Monoprint, Cyanotype, Mixed Meda on Arches 88 Paper, Courtesy of the Artist

Ann Guiliani is a painter and printmaker whose work serves as a self-protection mechanism deflecting incoming harmful energy. As a child, mark making for this artist provided a way to create and enter a world entirely of her making where curiosity was pursued through mixing materials. As an adult, this practice of world building has become a mechanism to protect her from the harmful effects of an unstable world. “We are bombarded with false narratives on steroids,” Guiliani has said. “We are on overload. As an artist, what do I do? Increasingly the need to create my own world and my own language has become more urgent and quite possibly a point of departure or a means of survival.” The artist works intuitively and employs chance to create works depicting her internal state. In Icon 1 Litigare, the frenetic energy Guiliani experiences from external stimuli reflects turbulence. “This is a litigious and confrontational society,” she says. “A confrontational stand that I was trying to ignore, surfaced and revealed itself in the final image.” The work is in dialogue with the traditional icon paintings of Christian art but evoke more of a disturbance than a “window to the divine.” “Litigare” in the title is the Italian verb “to argue” and is related to the English word “litigate.” In addition to the intense visual energy of the piece, the artist’s mixing of lithography, monoprint, and cyanotype processes aids in the creation of the feverish composition.

The global economic order and its local manifestations create many of the conditions that can make it difficult for us to challenge the established order. Rancière refers to the market incentivizing us to obey as “the beast.” He wrote that it “gets a stranglehold on the desires and capacities of its potential enemies by offering them, at the cheapest price, the most desirable of commodities – the capacity to experiment with one’s life as a fertile ground for infinite possibilities. It thus offers everyone what they might desire: reality TV shows for the cretinous and increased possibilities of self-enhancement for the malign.” Capitalism, essentially, absorbs dissent by emphasizing the opportunity we have to a freedom to acquire what we desire. That acquisition becomes a self-perpetuating cycle of our ever-increasing desire, our ever-customizable sense of identity, and our ever-insatiable consumption. Chasing our desires and always wanting more is the means by which a small elite achieves profit generation and wealth accumulation. And the wheels of this machine are greased with manipulated language.

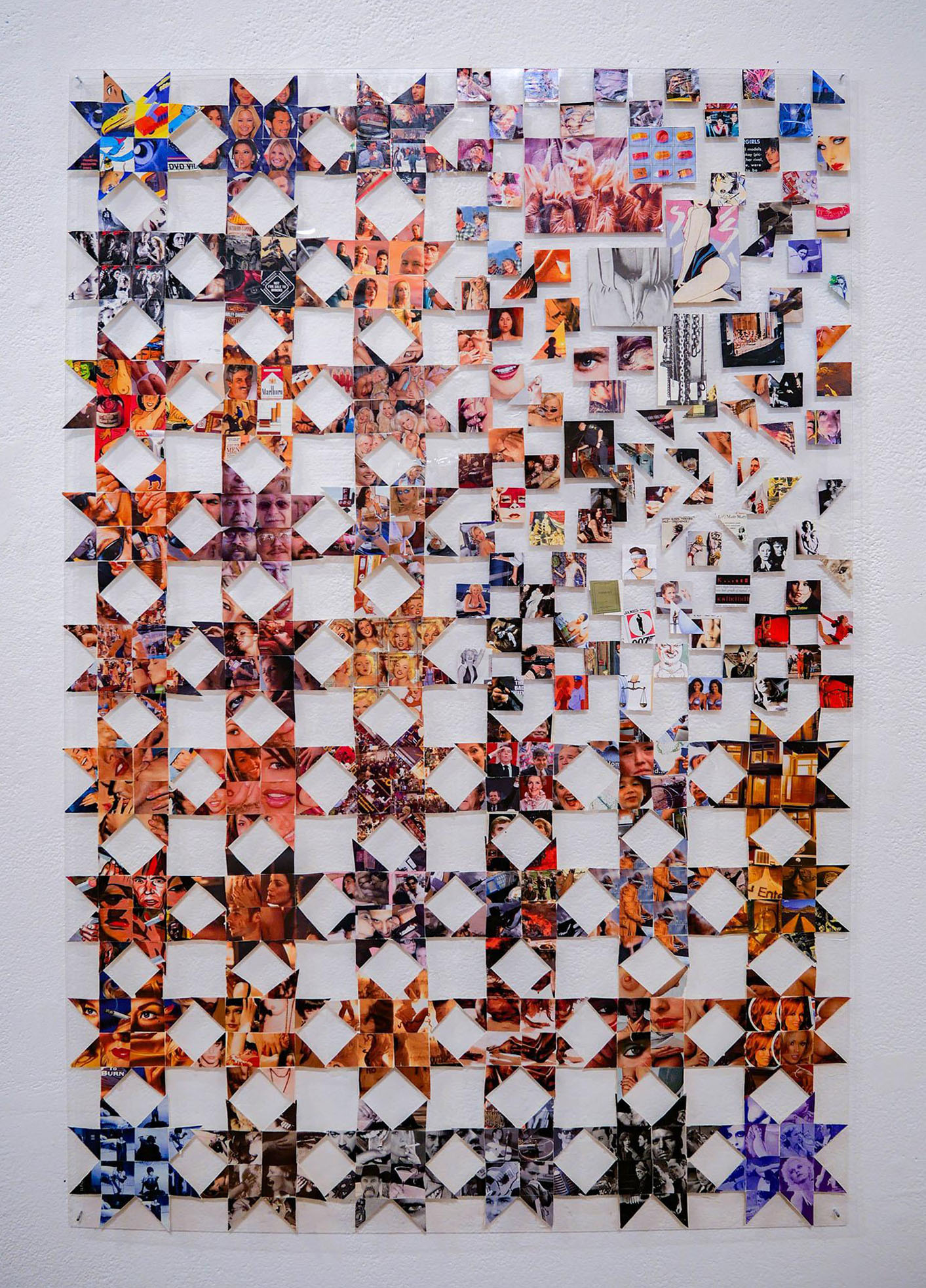

Annika Fricke, Post Babel Construct, 2025, Paper on Plexiglass, Courtesy of the Artist

Annika Fricke says her art “explores the loop of production, consumption, desire, and resistance that constitutes the American Dream.” She uses the visual strategies of quilting and the practice of collage to challenge and destabilize dominant narratives. “Much of my work draws from traditional American quilt patterns,” Fricke says. “These patterns were historically used to preserve stories and pass down generational knowledge and now serve as a structure for visual resistance. By integrating these forms in my collages, I connect histories of care, labor, and protest with the language of contemporary media. The result echoes the cycles of consumption and control that define American life.” Fricke takes images from popular culture, including Playboy Magazine, to confront power and value structures with regard to gender and identity. Collage is an adept method of making subconscious messaging visible because it presents a simple recontextualization of preexisting imagery. As a result, it both identifies and questions what has become normalized in society. Fricke asks: “Is the body still natural, or has it become an abstracted tool of political subjectification—detached, commodified, and redefined to reinforce dominant American ideologies?” In Post Babel Construct, she presents a semi-transparent quilt of cut up and folded pop culture imagery. In referencing in this work the Tower of Babel from the Judeo-Christian tradition, where god thwarted the human attempt to build a tower to reach heaven by sowing cultural division, Fricke disentangles manipulated messaging and shows how contemporary identify is composed of fragments significantly influenced by capitalist forces.

Scott David Isenbarger, Don’t Be A Hothead, 2025, Oil on Canvas, Courtesy of the Artist

Scott David Isenbarger is a painter whose works question contemporary notions of masculinity while excavating their origins. Isenbarger’s exhibited paintings are inspired by Francisco de Zurbarán’s ten paintings of the labors of Hercules circa 1634. “Zurbarán's paintings offer a somber, primitive vision of masculinity rooted in brute force and political power,” says Isenbarger. “Commissioned to glorify King Philip IV [of Spain], the paintings depict Hercules as an emblem of the monarchy's strength, stripping the myth of its deeper psychological complexity. The hero's journey is not one of self discovery, but a series of raw and brutal conquests, reflecting a narrow and archaic view of male power as something to be wielded for political gains.” Critiquing Zurbarán's painting Hercules and the Hydra, Isenbarger’s painting Don’t Be A Hothead shows a shirtless Hercules in boxer shorts in the moment before slaying the Hydra with a club when he’s assaulted from behind with a blowtorch by a man in camouflage. “Drawing from the flamboyant theatrics of professional wrestling and action movies… with the over-the-top aesthetic of the 90s,” Isenbarger says, “my paintings satirize the shift from a propaganda driven portrayal of masculinity to one driven by entertainment and commercialism, which parallels our contemporary culture and current political climate. The critique lies in the absurdity of the performance. The now pudgy Hercules, posed in overly dramatic lighting and donning MAD magazine-like facial expressions, pokes fun at the idea that true strength is simply a matter of external appearance, revealing how something once solemn and sacred can be reduced to a hollow spectacle.” In doing so, the artist calls our attention to the sense of masculinity that’s marketed to us as something we should emulate and can acquire. As with all advertising, we must remain aware of the positionality of who is glorifying this sense of masculinity and what incentive there is for them to try to get us to glorify it too.

There is no objectivity, all statements are slanted in some way. The difference between an individual expressing their subjectivity and an institution (a government, a corporation, etc.) doing the same is defined by intent and impact. Dutch artist, author, and curator Mieke Bal wrote “Like newspaper reports—a narrative genre—all narratives sustain the claim that ‘facts’ are being put on the table. Yet all narratives are not only told by a narrative agent, the narrator, who is the linguistic subject of utterance; the report given by that narrator is also, inevitably, focused by a subjective point of view, an agent of vision whose view of the events will influence our interpretation of them.” Whereas an individual may succeed in influencing one or a few people with their subjective point of view and that may result in those influenced to change what they believe (and, as a result, what they say or do), an institution’s subjective aim is to influence entire audiences, or even whole societies, with the intent to engineer mass actions to perpetuate its power. The “facts on the table” Bal spoke of are arranged and presented in specific ways to control narratives, manipulate inferences, and maintain positions of power.

Economist Edward S. Herman and linguist Noam Chomsky wrote the book Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of Mass Media in 1988. In it, they outline the role of mass media in the effective delivery of dominant narratives as well as the differentiated roles of the large, dominant institutions of power and smaller institutions perpetually struggling for any airtime they can get. Herman and Chomsky wrote “the large bureaucracies of the powerful subsidize the mass media, and gain special access by their contribution to reducing the media’s costs of acquiring the raw materials of, and producing, news. The large entities that provide this subsidy become ‘routine’ news sources and have privileged access to the gates. Non-routine sources must struggle for access, and may be ignored by the arbitrary decision of the gatekeepers.” This gatekeeping function the media performs is largely uncritical, despite the news agency’s self-styling as a “fact checking,” “keeping them honest” entity, especially when it comes to governments. “The media,” Herman and Chomsky wrote, “do not stop to ponder the bias that is inherent in the priority assigned to government supplied raw material, or the possibility that the government might be manipulating the news, imposing its own agenda, and deliberately diverting attention from other material. It requires a macro, alongside micro- (story-by-story), view of media operations, to see the pattern of manipulation and systemic bias.” Lutz’s criteria for identifying doublespeak is important when consuming news media, because it is safe to assume agents of the media have not completed a similar evaluation.

Jean Seestadt, Controlling Us, 2025, Fabric, Embroidery Thread, Courtesy of the Artist

Jean Seestadtcreates textile works that reflect on our experiences when we’re captive audiences to media that endlessly bombard us with skewed messaging from dominant institutions: airport lounges, doctor’s office waiting rooms, the DMV, etc. Seestadt says she “documents the gnawing indignities of institutional spaces and the silent fury they generate, with each stitch repetitively tallying the time we must spend in these places.” The artist uses textiles because they are soothing objects that comfort us in times we need protection and stability. The artist has said: “I use textiles to study banal, generic spaces: security lines and medical waiting rooms with fish tanks, daytime TV, and drab seating. There is a logic to these spaces – they are bright! they are airy! — that intentionally hides what they do. These spaces hold and manage people during their most vulnerable life moments; moments when they might employ textiles to manage parting, returning, pain, and healing.” In Controlling Us, Seestadt shows people waiting in line where frames depict incessant messaging fed to us in the “down time.” A black screen reads “Don’t be emotional,” TV screens show a CNN broadcast and a talk show, and a police officer is shown posing with his K9. She says she “bridges the everyday and unexpected, opening cracks and fissures in routines and spaces of control that effervesce with humor and crackle with tension.” Her work encourages us to pause when we are in these places of enforced docility and waiting to consider how the information thrown at us is framed, how it is linked to institutions through invisible threads, and what effect it has on us.

Given the acknowledgment that subjectivity is inherent in the delivery of a message (particularly impactful is the slant of large, powerful institutions), it is important to understand how things are framed. Framing is the way in which our inferences are intentionally influenced through presentation of material such as text and images. Bal wrote “Analyzing the way images are, and have been, framed helps to give them a history that is not terminated at a single point in time, but continues; a history that is linked by invisible threads to other images, the institutions that made their production possible, and the historical position of the viewers they address.” Understanding how the language of word and image is framed enables us to dissect, analyze, and interpret biased information fed to us. With the transparency achieved through this process, we can then recognize covert intentions. As examples, Herman and Chomsky noted that “powerful sources regularly take advantage of media routines and dependency to ‘manage’ the media, to manipulate them into following a special agenda and framework… Part of this management process consists of inundating the media with stories, which serve sometimes to foist a particular line and frame on the media… and at other times to help chase unwanted stories off the front page or out of the media altogether.”

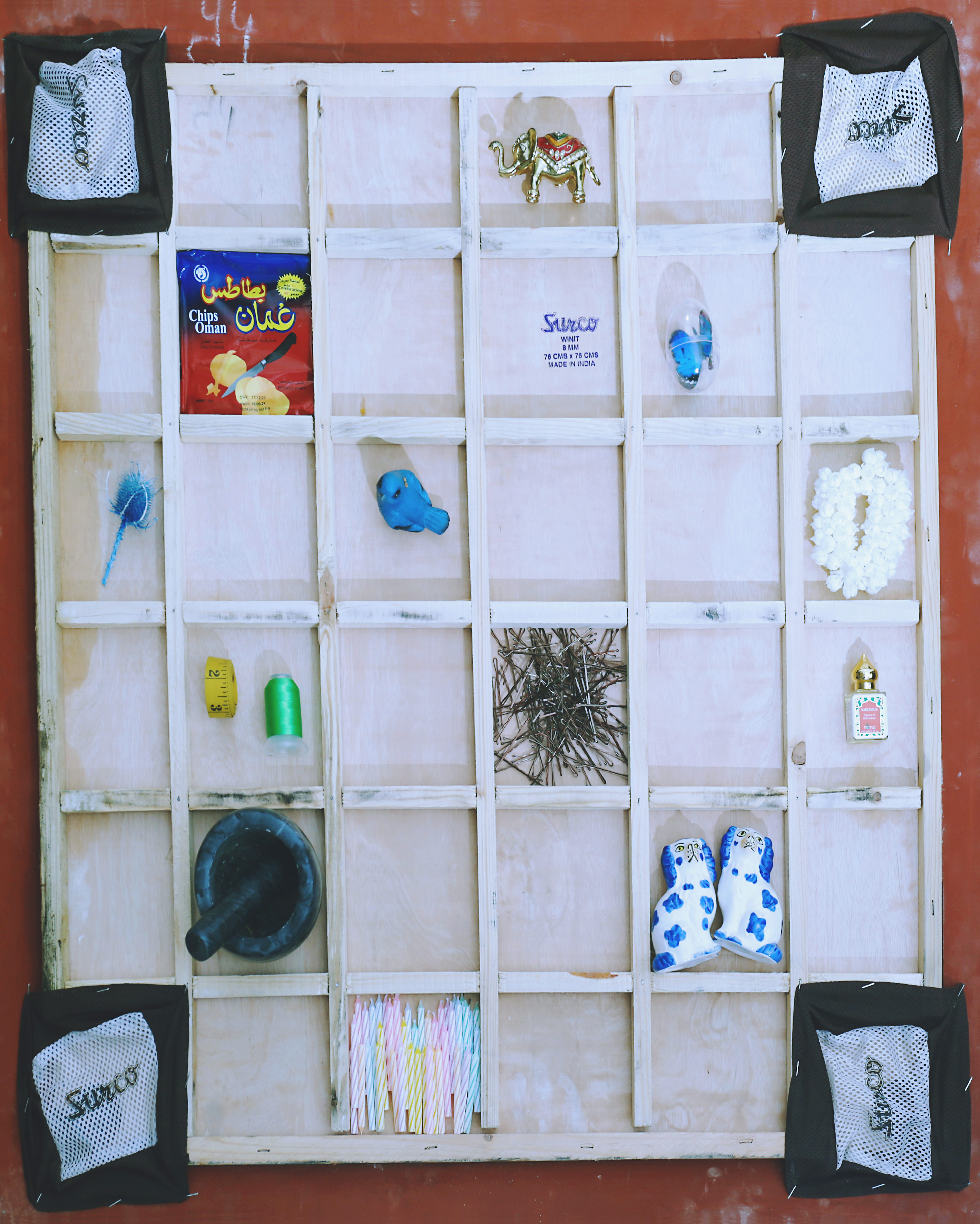

Nasrah Omar, Migration Repository, 2024, Inkjet Print on Archival Rag Paper, Courtesy of the Artist

Nasrah Omar uses photography and other mediums to intertwine advocacy, care, and cultural visibility in layered stories of migration. She maintains that borders and status hierarchies are social constructs that perpetuate human divisions through manipulation. Through her work, Omar shows that journeying is a shared human experience that leaves open the possibility for understanding and empathy. “Rooted in my lived experience as a first-generation immigrant with ties to India and a third-culture upbringing in Oman and America,” she says her work “draws on advocacy, ancestral memory, diasporic journeys, and collective imagination to build counter-lexicons… Against institutional framings that reduce immigrant life to statistics or burdens, the collaged tableaux and allegorical compositions function as counter-archives: they re-articulate grief, longing, and alienation into portals of tenderness, healing, and re-enchantment.” Her photograph Migration Repositoryshows a wooden construction grid of 36 receptacles. Some are empty and others contain objects ranging from candles and hair pins to a bag of chips from Oman and an elephant figurine. It shows what has been collected on a journey so far, leaving the empty spaces for materials yet to be collected when traversing future borders. ”By reimagining these boundaries as porous and dismantlable,” Omar says, “the work insists that another world is possible, one where histories, geographies, and futures are held together through solidarity and tenderness rather than control… By dislocating narrative away from flattening, the work resists the simplicity with which media and political actors often script immigrant lives, opening instead to multiplicity, complexity, and possibility.”

An additional complicit action of media agencies is the “curation” of images contextualized by “experts” who speak with authority about what we can understand from viewing those images. “What we see above all in the news on our TV screens,” Rancière wrote, “are the faces of the rulers, experts and journalists who comment on the images, who tell us what they show and what we should make of them. If horror is banalized, it is not because we see too many images of it. We do not see too many suffering bodies on the screen. But we do see too many nameless bodies, too many bodies incapable of returning the gaze that we direct at them, too many bodies that are an object of speech without themselves having a chance to speak.”

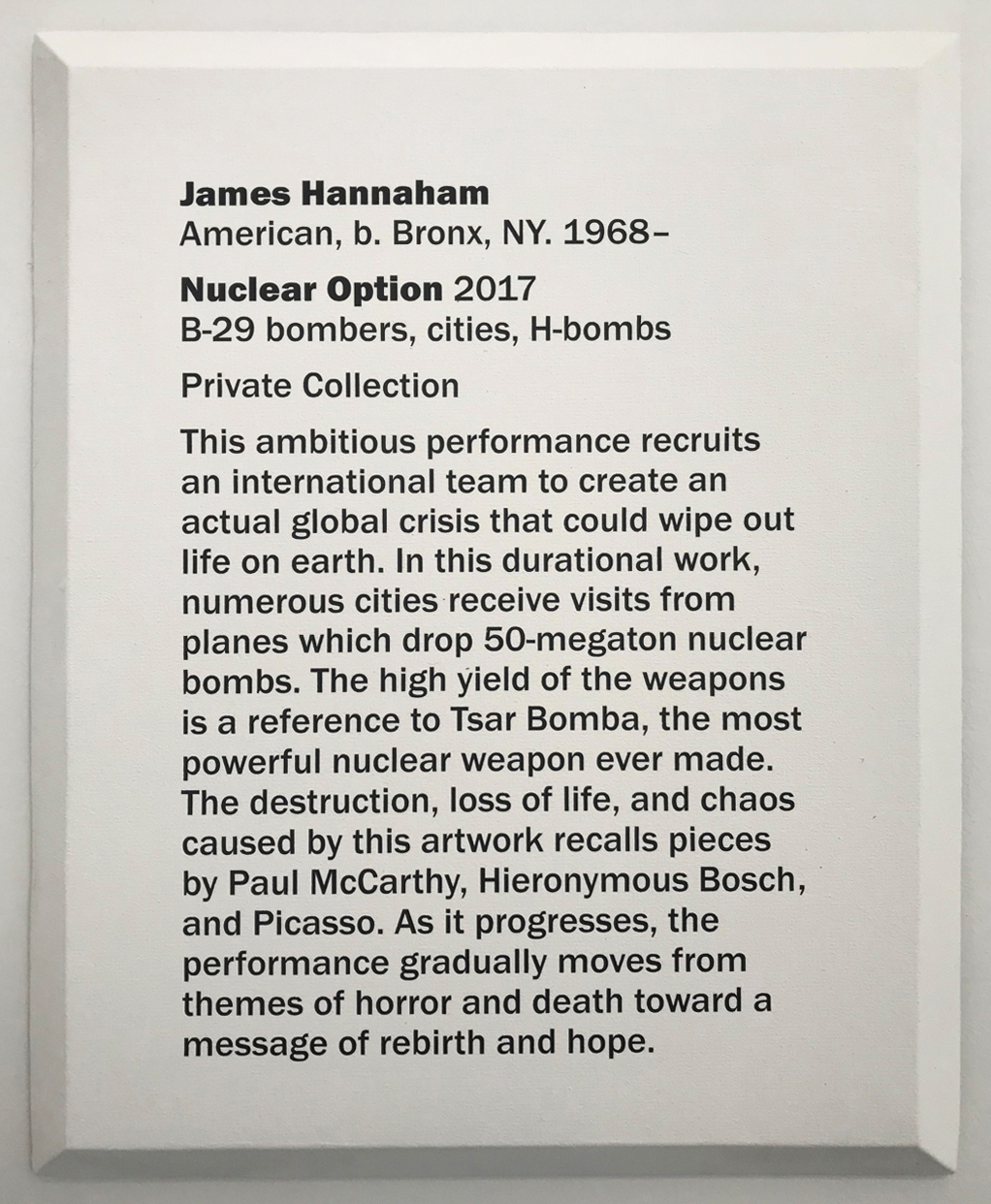

James Hannaham, Nuclear Option, 2017, Vinyl and Gesso on Canvas, Courtesy of the Artist

James Hannaham is an artist of words and uses satire to expose structures of power and their effects. In this artist’s exhibited work, Nuclear Option, positions of authority in both the art world and the war room are investigated. Hannaham’s painting is a canvas with beveled edges to mimic the form of exhibition panels and object labels, collectively referred to as “didactics,” in art museums. The curators who are often the ones to author these didactics hold positions of authority and how they position their words can reinforce hierarchies. Curators are often self-styled “experts” about what’s on view and their skewed interpretation of art can be seen as explaining what an artwork depicts and how the public can interpret it. In this work, Hannaham has made the didactics the art object. “The intention of this work,” he says, “has always been to subvert the authority of the institutions through satirizing the words they use to try to explain art, culture, and politics to us and thereby exposing the mechanics of that authority.” In Nuclear Option, Hannaham also critiques the way in which war is discussed in the media. In the painting the artist characterizes the bombing of cities as a durational performance moving from destruction to “a message of rebirth and hope.” Media commentators, like curators, often explain something to others, as if their perspective is all that is relevant. The presentation of news also prioritizes the perspective and interpretation of the correspondent and their “expertise” over the experiences of those directly terrorized by warfare.

These “experts” are often representatives of institutions of power that not only have a vested interest in how news stories are understood by the public, but that also are the source of the news to begin with. And Herman and Chomsky add, “If the articles are written in an assured and convincing style, are subject to no criticisms or alternative interpretations in the mass media, and command support by authority figures, the propaganda themes quickly become established as true even without real evidence. This tends to close out dissenting views even more comprehensively, as they would now conflict with an already established popular belief.” This endlessly churning machine of propaganda has been so thoroughly routinized it’s difficult to identify any news stories we can assuredly ascertain ourselves without being spoon-fed predefined narratives.

Tyler Alpern, Grand Olde Party, 2024, Oil on Canvas, Courtesy of the Artist

Tyler Alpern creates paintings loaded with subtle symbolism. His expressive style consistently evokes an emotional response through capturing the essence of an individual’s character. His painting Grand Olde Party flips the script on the conservative political party’s repressive policies. “The painting is a visual metaphor for the outdated, rabidly homophobic values, ongoing legislative bullying and personal attacks of the Republican Party on gay people and their families,” Alpern says. “I made it winter to emphasize the coldness and brutality.” Aside from the violence depicted in the painting it can also be interpreted as a subversion of Republicans referring to liberals as “tree huggers.” In this dark portrayal, he turns the table on the representatives of institutions of power and their largely unchallenged propaganda that encourages the brutalization of queer individuals. Alpern cites the following examples: “In 2022, Florida and other Republican led states passed many anti-gay, anti-trans laws and their school boards banned books and curriculum in attempts to turn back the clock and erase gay people entirely. In 2023, book bannings, laws against Drag and Trans healthcare continue the never ending crusade of hate.” In the fear-mongering of the Republican Party, publicly anxiety over trans athletes “invading” women’s sports is exploited. Conservatives in power are also exerting control through banning even discussion of civil rights in schools.

In addition to propaganda, narratives are also controlled through censorship. American philosopher Judith Butler identified several possible manifestations of censorship in her 1997 book, Excitable Speech: A Politics of the Performative. Her examples include “a dominant power that seeks to control any challenges posed to its own legitimacy,” “the use of censorship in an effort to build (or rebuild) consensus within an institution,” and “the use of censorship in the codification of memory, as in the state control over monument preservation and building, or in the insistence that certain kinds of historical events only be narrated one way.” All of these types of censorship can be in play simultaneously and, with the intentional inundation of news stories, it can result in us feeling paralysis with the intent to deter any kind of resistance. “In political calculations,” Butler said, “it is important not to underestimate the force of the desire to foreclose futurity. This is one reason that asking certain questions is considered dangerous, and why we live in a time in which intellectual work is demeaned in public life.” What she means by foreclosing futurity is the shutting down of possibilities for change. Politicians and others in power actively exploit public anxiety to push agendas preserving the status quo. The “intellectual work” of critical thinking is demonized at the same time, preempting resistance as part of a carefully crafted campaign to engineer obedience.

Societal norms are essentially codes of conduct (often unstated and unwritten and simply thought of as “common sense”) that silently program us by shaping what is acceptable thought and behavior. For Butler, the most implicit form of power is the illegibility of institutions’ intentions, namely governmental and corporate entities, defining and enforcing social norms undetected. By operating mostly invisibly, these actions mean challenging institutions of power is very difficult, particularly because to do so, one would have to challenge heavily entrenched societal norms.

Lulu Luyao Chang, The Red Star Is Rising, 2024, Glazed Earthenware, Synthetic Hair, Pigment Mixed Silicon, Plastic, Steel, Glue, Courtesy of the Artist

Lulu Luyao Chang is a multidisciplinary artist who challenges societal norms across multiple cultures. “I draw from personal experience to examine how invisible forces, political, social, and cultural, shape individual and collective realities,” she says. The artist was born in Japan, raised in China, and now lives in the US. Chang’s experience of living in multiple cultures reflects the consistent manipulation and suppression of information, albeit via very different approaches, with the same result: fortification of harmful, dominant political narratives. Her exhibited mixed media sculpture, The Red Star Is Rising, specifically references her experience growing up in China and it instills a disquieting and foreboding feeling in the viewer. “Growing up in China,” says Chang, “I experienced firsthand the quiet violence of censorship and ideological conditioning.” The piece appears to be a swing with messy organic forms that ooze over the edges and whisps of hair that jut out chaotically in multiple directions. And yet, the chains that suspend the seat and control its movement indicate an oppressive authoritarianism. Given its title, the work can be read as a critique of Chinese government control, but it also can reference state-sponsored fear-mongering of China in both Japan and the US. Chang characterizes her work as “a continuous exploration of what lies beneath the surface, what is hidden, distorted, or left unsaid, and how art can serve as both a site of resistance and a reimagining of new possibilities.” Challenging norms through art can be courageous as it involves taking the risk of societal ostracism.

Butler wrote, “A subject who speaks at the border of the speakable takes the risk of redrawing the distinction between what is and is not speakable, the risk of being cast out into the unspeakable.” Saying or doing something that challenges norms has the potential of altering what can be thought of as acceptable more broadly, not just for oneself, but for others as well. This is why norms are fortified by powerful systems, including threats of shaming, prosecuting, and abusing anyone who seeks to rock the boat. Art is often at the forefront of resistance to and subversion of norms, constantly taking risks to expand the limits of what is “speakable.”

Chanya Vitayakul, Everything I Would've Taught My Now Aborted Child, 2024, Silk Organza, Steel Rod, Steel Chain, Courtesy of the Artist

Chanya Vitayakul is an artist who works across design, installation, and sculpture. Their work “blends personal narrative with material investigation to examine how the body is written, held, and sometimes violated by external systems: gender, language, family, nationhood, medicine.” Vitayakul’s practice approaches the violence of language in these systems as having the capacity to both harm and defend a body. In their exhibited work, Everything I Would've Taught My Now Aborted Child, the artist embraces their vulnerability with regard to the taboo subject of abortion and rearticulates it as a method of resistance to abusive societal norms. In this defiantly vulnerable space where pain and closure intertwine, Vitayakul challenges what is “unspeakable.” In this work and others, the artist asks: What does it mean to be seen, and to survive that seeing?” In 2021, the state of Texas passed Senate Bill 8, which enables any citizen to bring a civil lawsuit against a medical professional or anyone else who “aids or abets” an abortion. While lawsuits cannot be brought against women seeking abortions, this law seeks to enforce an effective ban on abortions through state surveillance and punishment. “Making, for me, Vitayakul says, “amplifies voices where silence is imposed; it unsettles clarity, generating spaces where alternate readings, ruptures, and counter-narratives can emerge.”

In following norms, an individual goes unnoticed in the crowd. Subverting norms singles out the offending individual whose deviance is identified for “correction.” Norm fortification by powerful institutions is pursued by surveillance and enacted with punishment. In Discipline & Punish: The Birth of the Prison, Foucault wrote that “as power becomes more anonymous, and more functional, those on whom it is exercised tend to be more strongly individualized; it is exercised by surveillance rather than ceremonies, by observation rather than commemorative accounts, by comparative measures that have the ‘norm’ as reference rather than genealogies giving ancestors as points of reference; by ‘gaps’ rather than by deeds.” And in contemporary democratic society, punishment is often unnecessary, because the tug of the market is effective at co-opting dissenting individuals through consumption and brings them back in line by exploiting desires. Rancière wrote that democracy in this context is “the law of the individual concerned exclusively with satisfying her desires. Democratic individuals want equality. But the equality they want is that which obtains between the seller and the buyer of a commodity. Consequently, what they want is the triumph of the market in all human relations. And the more enamoured they are of equality, the more passionately they help bring about that triumph.” All paths lead the individual back to “normalization.” All norm-enforcing institutions from government and the media to education and health pursue preemptive punishment by anticipating resistance to their power and rendering it unnecessary through a combination of ensuring obedience and consumption. “The art of punishing,” Foucault wrote, “is aimed neither at expiation, nor even precisely at repression… The perpetual penalty that traverses all points and supervises every instant in the disciplinary institutions compares, differentiates, hierarchizes, homogenizes, excludes. In short, it normalizes.”

Sandra Cavanagh, Coding Citizenship 1, 2023, Archival Inkjet Print on Paper, Courtesy of the Artist

Sandra Cavanagh is an artist who works in many areas of pictorial media: drawing, painting, and printmaking. And yet, the consistent material she uses, across all processes, is narrative. The stories she tells through her work are often a reaction to sociopolitical events. Much of Cavanagh’s work touches on the impact of disciplinary institutions that contrast, separate, stratify, assimilate, and marginalize. Through her art, she responds to these actions by translating complex experiences into tangible forms that others can interpret and respond to with their own experiences. The artist was born and grew up in Argentina during a period of political chaos, censorship, and state-sanctioned violence. Cavanagh bore the burden of carrying this experience with her as she moved from Argentina to the US to the UK and back to the US. In traversing multiple boundaries, cultures, and political systems, themes of migration and citizenship are, like narrative, malleable materials with which she works. In describing her works in this exhibition, she said Coding Citizenship “resulted from collaging elements of state, identity, documentation and self-portrait drawings.” Those immigrating to the United States are often demonized by politicians for all real and imagined societal ills, with threats of violence not unlike state actions in the artist’s country of origin. With regard to immigration, politicians of all persuasions in this country have contributed to an efficient machine of intimidation, detention, and deportation to instill fear and maintain disproportionate systems of power. “I think primarily the artist is a mirror to their time and community,” she says. “If political, they’re about a societal viewpoint, if abstract they’re about an artistic viewpoint, if biographical they’re about a psychological viewpoint.” In considering the narrative, scope, and style of Cavanagh’s work, it’s clear her viewpoint is comprehensive and her work often thwarts the systemic oppression of normalization.

“Normalized” individuals are kept in place for the purpose of keeping the machinery of retaining positions of power by dominant institutions and retaining profits for the wealthiest operating them. In his discussion of disciplinary measures passed from one type of institution to another, Foucault said, “These were always meticulous, often minute, techniques, but they had their importance: because they defined a certain mode of detailed political investment of the body, a ‘new micro-physics’ of power; and because, since the seventeenth century, they had constantly reached out to ever broader domains, as if they tended to cover the entire social body.” From the military and institutions of incarceration, this “micro-power” has become, over time, decentralized. Hospitals, places of employment, and schools contribute to this system of obedience. The totality of this system conditions the behavior of an entire society through thorough and microscopic disciplinary actions. “Discipline is no longer simply an art of distributing bodies, of extracting time from them and accumulating it,” Foucault wrote, “but of composing forces in order to obtain an efficient machine.” The result is a smoothly operating, engineered society.

Each individual cog of this machine plays an optimized role. The output of the overall, aggregate process is far greater than the sum of individual performances. Foucault argued that the dreams of an idealized society from the time of the Enlightenment in the 1700s were realized not through empowering autonomous individuals, but instead through obedient, productive cogs. He emphasized that this dream’s “fundamental reference was not to the state of nature, but to the meticulously subordinated cogs of a machine, not to the primal social contract, but to permanent coercions, not to fundamental rights, but to indefinitely progressive forms of training, not to the general will but to automatic docility.”

Isabella Covert, Leak Ligation, 2025, Nylon, Latex, Clay Teeth, Forceps, Courtesy of the Artist

Isabella Covert makes soft sculptures and installations that turn the body inside out. These works challenge hegemonic systems that prioritize standardized, docile, cookie-cutter bodies trained to perpetuate this system. “Communicating the interplay of excess political control and gendered dynamics,” she says, “the entangled forms in my work abstract the body and its capabilities. Permeating a paradoxical allure with materials like latex and hair, my work serves as a surrogate for the body and the afflictions of bodily containment.” The bodies her work gives birth to are both a result and perpetuator of instability. “They violate rules imposed upon materials - tampering with tactile relationships that promote rapid aging, discoloration, and festering,” Covert says. In her exhibited sculpture, Leak Ligation, a bulbous, serpentine body has excreted a leaking form still tethered to its dental orifice while pincers protruding from its other phallic end move to surgically sever it. The form is as disturbing as it is erotic and it arouses a tension between natural biological evolution and synthetic biological engineering. Is it either or both? Through her work, Covert says she “investigates liberation and contradiction within synthetic biology.” This refers to a field of science where new biological parts and systems are engineered (genetically modified organisms, growing materials from cells, DNA programming, etc.). The possibilities of this speculative field include both the ethical problem of eugenics and the promise of expanded notions of identity. One of the questions Covert poses through her work is “Through developments of artificial wombs and egg harvesting, will advanced technology hold the ability to liberate women from the expectations of childbearing?” Time will tell, but, if the answer is “yes,” it’s unclear if that will mean the farming of mindlessly efficient cogs or fiercely autonomous mutants ushering in a reimagined, utopian reality. “I work in a space where I can pick at thoughts and potentialities of the body in the current era,” Covert says, “thinking critically about who and what we are becoming.”

Over time, the ongoing, “permanent coercions” embedded in the current societal machine have yielded an even more efficient system through the subconscious training of individuals to self-police. “From the master of discipline to him who is subjected to it,” Foucault wrote, “the relation is one of signalization: it is a question not of understanding the injunction but of perceiving the signal and reacting to it immediately.” In other words, the relationship between disciplinary system and individual cog is not one of dialogue or reasoning, but instead a coded set of cues, like a whistle to a dog, that prompts the desired conditioned behavior without the individual thinking critically about the meaning or purpose of the command. An example is standing to recite the pledge of allegiance with your hand placed over your heart at the beginning of each day at schools across the United States.

KR Windsor, Identity Crisis, 2025, Giclée Print of Digital Collage on Archival Paper, Courtesy of the Artist

KR Windsor is a designer and digital artist whose primary raw material is the written word. “Words have shadows,” he warns. “They are hidden meanings or ambiguous associations that refract how words are received and understood.” While some of these “shadows” are innocuous and empowering, such as in poetry, they have become increasingly insidious. Many of the impacts of the harmful weight of the written word have been codified as policy via the federal register and Truth Social alike. Racism, misogyny, transphobia and more are not only written into laws; they have become cerebral growths where we have internalized harmful policies, resulting in automated self-oppression. About his exhibited work Identity Crisis, Windsor says “One aspect of the ‘American experiment’ is best expressed in the unofficial motto E pluribus unum—“Out of many, one”… The aspiration of our immigrant nation, and the dream of success and a good life, has been fundamental to our identity, expressed here in 27 of the most spoken languages in the United States. Today, this cohesion is failing as the notion of being an immigrant is demonized, and our… collective identity is challenged and fractured.” Like a virus, our internalized oppression spreads as we’re encouraged to police each other. “At the core of my work,” Windsor says, “is subverting the form–meaning construct of these abstract glyphs we imbue with intention, interrogating how they express the historical record we’re left with, but also mediating the relationships we have with institutions, other cultures and each other.”

Foucault said that discipline “makes” individuals and is exercised by “a modest, suspicious power, which functions as a calculated, but permanent economy… The success of disciplinary power derives no doubt from the use of simple instruments; hierarchical observation, normalizing judgment and their combination.” The powerful institutions of society thus mold the individuals needed to perpetuate domination and those individuals are intentionally molded to police themselves and others so that the maintenance of the machinery requires little direct intervention. Foucault argued that “Discipline makes possible the operation of a relational power… Thanks to the techniques of surveillance, the ‘physics’ of power, the hold over the body, operate according to the laws of optics and mechanics.” Obedience is decentralized and is perpetuated through relationships between individuals, such as between supervisor and employee. Because it is understood that surveillance is constant, the individual has internalized compliance with expected behavior.

Kasia Ozga, Life Jackets, 2020, Soft Sculpture, Photographs of Human Skin Printed on Vinyl, Recycled Ribbon, Foam Stuffing, Courtesy of the Artist

Kasia Ozga is a sculptor and installation artist whose work begins and ends with the human body. She collects and gives new life to the skins we shed from discarded garments to former lives. “I treat the products of our culture as physical remains of our bodies and explore how we generate objects as concrete extensions of ourselves,” the artist says. “With man-made forms, materials, and processes, I extend, inhibit, and modify elements of the human body.” On subjects ranging from migration to labor, Ozga also questions whose bodies are present and empowered and whose are hidden and silenced. At the core of her work is the investigation of the result of relational power, the horizontal human-to-human interactions between us that are skewed to vertical hierarchies. Her exhibited series of soft sculptures called Life Jackets are standard flotation devices worn for safety in the water for which she sewed together excess vinyl (on which was printed zoomed-in imagery of the skin around eyes of anonymous elderly volunteers) left over from another project and reclaimed, locally-sourced multicolor ribbons. About this work, Ozga says, “The personal flotation devices continue my exploration of sea passage, borders, and access to new horizons while working with the metaphor of human skin as a form of protection and a source of unequal treatment of travelers and migrants, alike… When used, each personal flotation device is an extension of a real physical body; here the boundary between the tool/garment and the user is intentionally blurred.” When grouped together as they are exhibited here, they enter into dialogue with the barely differentiated suits in corporate stock photography depicting “diversity”. Indeed, flotation devices such as these are made to be homogenized and yet, the skin of a person who wears one is more obvious in its difference. For example, if we assume that life jackets such as these are standard and equal in all disasters at sea, were those for the five people aboard the imploded Titan submersible in 2023 the same as ones for the 3,105 migrants killed in shipwrecks in the Mediterranean that same year? Ozga asks a similar question: “are all equally likely to get saved in times of need?”

As a result of the efficient system of compliance with expected behavior governed by dominant institutions, deviation from norms and outright resistance is preemptively deterred. “Discipline,” Foucault wrote, “could reduce the inefficiency of mass phenomena: reduce what, in a multiplicity, makes it much less manageable than a unity; reduce what is opposed to the use of each of its elements and of their sum; reduce everything that may counter the advantages of number. That is why discipline fixes; it arrests or regulates movements; it clears up confusion; it dissipates compact groupings of individuals wandering about the country in unpredictable ways; it establishes calculated distributions. It must also master all the forces that are formed from the very constitution of an organized multiplicity; it must neutralize the effects of counter-power that spring from them and which form a resistance to the power that wishes to dominate it: agitations, revolts, spontaneous organizations, coalitions.” Dominant institutions break up possible resistance to their power through mechanisms such as enforcing rules against “trespassing” and “vagrancy,” setting public curfews, dispersing and/or arresting protesting individuals, etc.

Cecil W Lee, They Should Have Known, 2025, Soft Sculpture, Ink Print of Computer Evolved Composition on Canvas, Courtesy of the Artist

Cecil W Lee refers to his work as “Computer-Evolved Art” where he digitally collates layers sourced from painting, photography, and mixed media to construct an evocative visual narrative. He’s been experimenting with art and technology since he first obtained a computer in the 1980s. The complexity of his work has evolved over time and it has developed incrementally. He often revisits earlier work as both his art’s meaning and his perspective on it change over time. About his exhibited composition They Should Have Known, Lee says, “The men are uniform yet distinct, resisting complete assimilation. Their presence before the stark wall and national flag represents a warning of enforced compliance and retribution.” The men are predominantly depicted in grayscale, yet are surrounded by color. Is their destiny collective or individual? Do their stories take into account their individual complexities or are their characters viewed in terms of black and white? As Lee indicates, the American flag is a symbol of the federal government, an institution of incredible power dictating “enforced compliance” in a system of “justice” benefitting only the most privileged and promising “retribution” if there’s any dissent. Institutions of discipline from the American criminal justice system to higher education ensure predictability by neutralizing the spontaneous organization of bodies: those labeled loiterers or trespassers, unionists striking for better pay and/or working conditions, those protesting and demanding divestment from genocidal governments, and the list goes on. “I have always looked for new ways of seeing and speaking through images, including the resistance of institutionalized distortions,” says Lee. “If language can imprison thought, art can unfasten it. I like to think of my work not as answers to questions but shifts in paradigms.”

The preemptive disempowering of dissent is felt differently by individuals and groups at different points along the political spectrum, but the end result is effectively the same. Rancière broke this down into the areas he defined as programmed responses felt by right-wing vs. left-wing to the orchestration and enforcement by “the beast” of the overarching political and economic system. “Right-wing frenzy warns us that the more we try to break the power of the beast, the more we contribute to its triumph.” Those on the conservative side of the spectrum perceive resistance to “the beast” as dangerously self-defeating. Attempts to change the system are prevented by the fear-mongering tactic of equating resistance with evil. For example, powerful institutions imply that an alternative to the current system will result in unwanted harm to individuals on the right and that advocating change is contradictory to traditional values of the church and the family. “Left-wing melancholy invites us to recognize that there is no alternative to the power of the beast and to admit that we are satisfied by it.” Those on the liberal side of the spectrum perceive resistance to “the beast” as futile and that transformation is not really possible. Attempts to change the system are thwarted through disillusionment. For example, powerful institutions simply ignore criticism and the left gives up when transformation isn’t realized simply through demonstrations.

So, what is one to do about this imposing system of manufactured confusion, manipulation, and obedience? Paralysis from how overwhelmingly intricate and pervasive the system can seem is the intended effect. To resist feelings of resignation to the inevitability of the system, one must use their voice strategically and stay motivated by constantly remembering the effects of “the beast” on you and your community.

Clark Stoeckley, Reimaging Police Precincts, 2022, Inkjet Print of Digital Collage, Courtesy of the Artist

Clark Stoeckley is an interdisciplinary artist whose work challenges oppressive systems acting to subdue us into submission. “For me,” he says, “art is not the end product. It is merely a tool for achieving social justice. I start with this in my mind and then work backward, doing whatever is necessary – drawing, painting, photography, video, design, or performance – to realize that vision. My art connects utopian ideals with everyday life with the hope of inspiring action for change. I am always looking to reach people beyond the art world, as my work is often best experienced in public spaces like our streets or the Internet.” In his project Reimagining Police Precincts, Stoeckley engages in collective action to combat individual feelings of self-defeat and disillusionment and envision an alternative future. He describes the project as “a series of speculative designs that propose transforming precincts—symbols of state control—into sites of community care… Police stations are framed as protectors of order, yet their very structures embody exclusion, surveillance, and force. By redesigning them as spaces for libraries, clinics, or gardens, the project functions as a counter-language, one that insists on alternative futures not yet sanctioned by policy or precedent.” Stoeckley’s argument that investment in affordable housing, arts and recreation programs, education, and job creation results in reduced crime rates in those communities is supported by a number of studies. The artist is seeking support to build an augmented reality smartphone application that replaces signage identifying buildings as police stations and prisons with the signage of entities improving quality of life and providing a sense of belonging. “Just as smartphones have allowed us to document and disseminate videos of police brutality and murder,” Stoeckley says, “we hope to utilize these devices to visualize the abstract concepts of prison abolition and police divestment.” Projects like this transform spontaneous collectivity and a radical reimagining of the possible to create solutions to problems inherent in our current system.

Rancière’s solution is dissensus: “What there is are simply scenes of dissensus, capable of surfacing in any place at any time. What ‘dissensus’ means is an organization of the sensible where there is neither a reality concealed behind appearances nor a single regime of presentation and interpretation of the given imposing its obviousness on all… every situation can be cracked open from the inside, reconfigured in a different regime of perception and signification. To reconfigure the landscape of what can be seen and what can be thought is to alter the field of the possible… Dissensus brings back into play both the obviousness of what can be perceived, thought and done, and the distribution of those who are capable of perceiving, thinking and altering the coordinates of the shared world.” What Rancière is suggesting is that we simply remember we are capable of thinking and acting and that we intervene accordingly using our creative talents to oppose the system that perpetually denies our agency. One doesn’t have to fully understand or take on the entirety of the system. Waiting for the ideal theory, leader, or revolution only benefits institutions of power and their continued domination of you.

One approach to making history in building a new system can start by effectively using the language of fiction. What does “fiction” mean and how can it change things? Rancière explained: “Writing history and writing stories come under the same regime of truth. This has nothing whatsoever to do with a thesis on the reality or unreality of things. On the contrary, it is clear that a model for the fabrication of stories is linked to a certain idea of history as common destiny, with an idea of those who ‘make history’, and that this interpretation of the logic of facts and the logic of stories is specific to an age when anyone and everyone is considered to be participating in the task of ‘making’ history. Thus, it is not a matter of claiming that ‘History’ is only made up of stories that we tell ourselves, but simply that the ‘logic of stories’ and the ability to act as historical agents go together. Politics and art, like forms of knowledge, construct ‘fictions’, that is to say material rearrangements of signs and images, relationships between what is seen and what is said, between what is done and what can be done.” A function of art is using what Rancière refers to as “fiction” to imagine the possibility of a different future. Using art to assert what can be thought, said, and done, in itself, can alter our understanding of reality and enable the change necessary to “make history” to chart a new course forward.

Don’t wait until you have the “right vision” or “right voice.” There is no correct way to see or speak. In 1967, American art critic Michael Fried wrote about the relationship between a viewer and a contemporary artwork: “The beholder knows himself to stand in an indeterminate, open-ended—and unexacting—relation as subject to the object on display.” While Fried meant this as a criticism of what would eventually become known as postmodern art, it can be viewed as foresight into the power of contemporary art. The lack of a single way to see an artwork, as had been the case with modern art, encourages a viewer of postmodern art to look from multiple angles and think about their own relationship to the artwork, how their subjective position alters what the work means to them, and how the artwork impacts the way they see the world and themselves in it. This interaction, and its potential, is the greatest strength of contemporary art: it enables new ways of seeing.

Sean Riley, Foretold, 2025, Oil on Canvas, Courtesy of the Artist

Sean Rileyis a painter whose abstract compositions prompt the viewer to look—and look again, this time closer. “In my work,” he says, “visual perception is treated not as a static recording of the world but as something unstable, provisional, and constantly shifting.” Riley’s work asks you to look from another angle and question not only what you are seeing, but also how what you see has changed. “I build my paintings through layers of paint, marks, and fragments of text that accumulate like sediment or graffiti. These traces dissolve into fields of color and form, producing surfaces that resist singular interpretation. From up close, details appear tactile and intimate; from a distance, they flicker between coherence and collapse. This oscillation mirrors the instability of language itself, where meaning is never fixed but always subject to revision, distortion, or reinterpretation.” In a subtle way, his work, while aesthetically pleasing, instills a sense of disquiet. In addition to inviting the viewer to look closer and from multiple angles, it suggests a slower read as well. The longer the look, the more comfortable you are with discomfort and unlearning the expectation of questions leading to answers. Riley says, “My paintings exist between artifact and event—surfaces that hold the memory of their making and invite slow, careful looking. Each one is a record of layered moments: paint is applied, obscured, and revised until it becomes not just something to look at, but something to look into… They ask viewers to slow down, to inhabit uncertainty, and to engage with the instability of seeing itself—where illusion meets material, and where each canvas becomes a container for memory, time, and the possibility of transformation.”

Butler mused about how speaking can impact politics by asking, “Does the assertion of a potential incommensurability between intention and utterance (not saying what one means), utterance and action (not doing what one says), and intention and action (not doing what one meant), threaten the very linguistic condition for political participation, or do such disjunctures produce the possibility for a politically consequential renegotiation of language that exploits the undetermined character of these relations?” This inconsistency of language provides an opportunity for change. Language has always been and continues to be unstable. Art, as a kind of language, has the power to reinterpret and rearticulate relationships between the individual and established norms, providing a substantial opportunity to resist institutions of power and the dominant narratives they shout. Just as art enables new ways of seeing, it amplifies our voices. Art provides the platform to put us on a level playing field so that we can shout back louder.

Rancière said it most succinctly: “The images of art do not supply weapons for battles. They help sketch new configurations of what can be seen, what can be said and what can be thought and, consequently, a new landscape of the possible.” Art, as an unstable language, is powerful because its impact is uncertain, full of potential for challenging harmful dominant narratives. If we can see ourselves as capable of enacting change, we can use our voices to disrupt today’s system of doublespeak and discipline. We face a future full of possibilities. It’s time to speak and to act.

About the artists:

Tyler Alpern is an artist, a painter, an instigator, an educator and historian. His artwork reveals that he admires the unusual. Meeting pioneering artists Don Bachardy and Elver Barker, brought together his love of art and deep interest and creative research in hidden gay history. His formal education took him from Los Angeles to Rome, and back to Colorado to earn his MFA. He’s authored some books and has had numerous exhibitions of his paintings. The Library of Congress has preserved a digital archive of his work and career because of "its cultural and historic significance." His works and collaborations have been included in exhibitions at the Kinsey Institute and are in its permanent collection as well as belonging to the Museum of Boulder. He is based in Boulder, Colorado.

Web: tyleralpern.com

Instagram: @tylerjalpern

Sandra Cavanagh began her career in 1997, after completing a Foundation in Fine Arts and a BA degree from the Kent Institute of Art and Design in the UK. In the time since she has maintained a consistent practice and developed a large portfolio of work to include paintings, drawings and prints. She sustains a mostly narrative focus, often as a reaction to sociopolitical events with the intention of codifying ideas and feelings. She has often worked in series, creating pictorial storylines with some urgency to exhaust the subject and form to the point of understanding or unburdening herself of it. Born in Argentina, She studied Social Sciences at the University of Belgrano in Buenos Aires before emigrating to California and later to the UK. Her work has been exhibited across the US as well as in Italy. She is based in Brooklyn, New York.

Web: sandracavanagh.com

Instagram: @sandra_cavanagh_artista

Lulu Luyao Chang is a multidisciplinary artist working across installation, sculpture, and video. Her practice explores themes of social norms, repression, and the complexities of identity. In 2022, she was awarded the ArtTable Fellowship and served as a panelist for The State of LGBTQ in China organized by The China Project. Her solo exhibition at the Chinese American Arts Council in New York City in 2024 was reviewed in IMPULSE Magazine. Her work has been featured in several prominent art fairs, including Art Fair | Detroit, Zero Art Fair in upstate New York, and group shows at Latitude Gallery, IRL Gallery, LatchKey Gallery, etc. in New York City. Her video artwork has been screened at The China Project in NYC and Aotu Space in Beijing. She holds a BA in Art History from the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing and an MFA from the School of Visual Arts in New York. She is based in Chicago, Illinois.

Web: lululuyaochang.com

Instagram: @6u6usaferoom

Charles Compo is an internationally recognized painter, composer, and multi-instrumentalist. Though long immersed in the arts, he turned his primary focus to painting at age 60 and has since emerged as a powerful voice in contemporary abstraction. His work explores psychological depth, subconscious narratives, and the emotional layers of modern life through a vivid language of surreal forms, cryptic symbolism, and expressive color. He worked as an assistant to Andy Warhol and collaborated with filmmaker and artist Harry Smith. These experiences—alongside his involvement with avant-garde jazz figures like William Hooker—deeply informed his multidisciplinary practice. His paintings have been featured in more than fifty juried exhibitions across the US and Europe. He is based in New York City, New York.

Web: compoarts.com

Instagram: @compoarts

Isabella Covert is a painter and sculptor. Referencing body horror and the boundary-less nature of the body, her work examines the relationship of reproducing bodies within current biopolitical frameworks. Prodding at expanding posthuman potentialities of the body, she investigates liberation and contradiction within synthetic biology. She received a BFA from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 2023 and is currently an MFA Candidate and Graduate Fellowship recipient at the Savannah College of Art and Design. Her work has been exhibited across the US. She is based in Savannah, Georgia.

Web: isabellacovert.com

Instagram: @isacov.art

Annika Fricke works with found media—papers from the trash, Playboy and Overdrive magazines—selecting images through instinct and critique. She builds geometric compositions rooted in traditional American quilt patterns, long used to tell stories of lineage and cultural resistance. Inspired by Paul Preciado’s essay Pharmaco-pornographic Politics: Toward a New Gender Ecology, she examines the subjugation of women in mass media and popular culture. Through this archive of American symbology, she cuts, displaces, and reconstructs identity. Her work explores the loop of production, consumption, desire, and resistance that constitutes the American Dream. She received a BFA from Pratt Institute in 2025. She is based in Brooklyn, New York.

Instagram: @catg1rl4evr

Ann Guiliani works to catch fleeting moments in constant change to freeze them and revisit the images to see it in a different way. She is constantly painting and printmaking. Early exposure to the arts helped to formulate her approach to art, which is one of inclusivity and creative freedom. She was the first in her family to finish high school and go on to college at what is now Montclair University. While studying at New York University in the 1960s she was introduced to theories of chance, which have deeply impacted her work. In the 1980s, she taught at Cape Cod Community College and she received her MFA from the University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth in 2000. Her work has recently been exhibited in many exhibitions in Massachusetts and is in several public and private collections in the US, Europe, Russia, and Asia. She is based in Ithaca, New York.

Instagram: @annguiliani9

James Hannaham is a writer and visual artist. His novel Delicious Foods won the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction, the Hurston/Wright Legacy Award, and was a New York Times Notable Book. He has shown artwork at The Institute for Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University, Kimberley-Klark Gallery, Open Source, and other venues. His most recent novel, Didn’t Nobody Give a Shit What Happened to Carlotta, won the Ferro-Grumley Award from the Publishing Triangle, a second Hurston/Wright Legacy Award, and was also a New York Times Notable Book. Honors include a Guggenheim Fellowship and numerous residencies, among them Yaddo, MacDowell, and Fundación Valparaíso. He is based in Brooklyn, New York.

Web: jameshannaham.com

Instagram: @thespectacleisreal

Scott David Isenbarger is a painter who makes large, colorful paintings that draw heavily from postmodern and surrealist histories. His enigmatic compositions utilize archetypal humans and animals within familiar yet otherworldly spaces. He employs parody and satire with strong sugary colors to act as a foil to the recurring themes of misguided masculinity and apathy. He is interested in spaces of the unconscious, dream spaces, liminal spaces, and the characters that reside therein. Furthermore, he is intrigued by how these personal mythologies inform and affect identity. He received a BA in English and BFA in painting from Indiana University and an MFA from the San Francisco Art Institute. He has exhibited in museums and galleries nationally, and has artwork in several private collections. He is based in Kerhonkson, New York.

Web: isenart.com

Instagram: @isenkunst

Cecil W Lee is an artist and writer creating what he calls Computer-Evolved Digital Compositions. His work grows from photography, painting, and mixed media, all reworked through layers of digital refinement. Over time, he has built a body of work ranging from abstract and figurative to macabre, surrealist, and futuristic themes, reflecting his interest in transformation and storytelling. He purchased his first computer in the 1980 and quickly immersed himself in both the major applications of the day and the emerging online world of AOL. By the early 1990s, as software such as Photoshop and Illustrator became more accessible, he began experimenting with photography, painting, and mixed media as raw material for digital transformation. While his use of color and shading is striking, his compositions reach for something more elusive: a speculative space where identity, memory, and imagined futures overlap. He recently completed a coffee-table book, Obsession with Change: A Look at the Future from the Beginning. He is based in New York City, New York.

Web: cecillee.com

Instagram: @cecilwmlee

Nasrah Omar is an interdisciplinary artist working across photography, installation, XR, and collage. Through imaginative world-building, she cultivates healing paracosms that explore visibility, connection, and regeneration. Drawing on the South Asian diaspora, ecology, ritual, folklore, and technology, she creates layered visual landscapes that open pathways toward decolonial futurities. Her practice is rooted in the metaphysical and psychic dimensions of space, memory, and migration. Her work has been exhibited across the US as well as in Italy and the UK. She is a recipient of the Image Equity Fellowship from Google, the Culture Push Fellowship for a Utopian Practice, the New York Foundation for the Arts New Work Grant, and the SUGi x Nava Contemporary New Nature Award. She holds a BFA in Photography from School of Visual Arts and an MA in Photography from the Royal College of Art. She is based in New York City, New York.

Web: nasrahomar.com

Instagram: @Nasrah__Omar

Kasia Ozga is a Polish/French/American sculptor and installation artist. Born in Poland, she grew up in the Midwest, and studied in Boston, Cracow, and Paris. In her work, she reuses, revalues, and reanimates mass-produced materials into singular artworks and inverts associations we make with different types of waste. She has participated widely in residencies in Europe and North America and is a former Kosciuszko Foundation Fellowship recipient, Harriet Hale Woolley grantee from the Fondation des Etats-Unis, Jerome Fellowship recipient at Franconia Sculpture Park, and Paul-Louis Weiller award recipient from the French Académie des Beaux-Arts. Her work has been exhibited in over 15 different countries with significant Public Art Commissions. Currently an Assistant Professor of Sculpture at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, She has received a BFA from Tufts University, an MFA from the Jan Matejko Academy of Fine Arts, and a PhD from the University of Paris 8. She is based in Greensboro, North Carolina.

Web: kasiaozga.com

Instagram: @KasiaOzgaArt

Sean Riley is a painter whose work exists between artifact and event—they have surfaces that hold the memory of their making and invite slow, careful looking. His recent works feature a vessel-like form that serves as a container for marks, colors, lines, and fragments of text. This form can be read as a jar, a shield, a portal—at once enclosing and opening - it gathers information while also suggesting passage, as though viewers might step through the image into another space. His work has been shown in solo and group exhibitions throughout the Northeast US. He has received grants from the Joan Mitchell Foundation, The Rhode Island State Council on the Arts, and the Berkshire Taconic Foundation and has been an artist-in-residence at the Joan Mitchell Center, Yaddo, and the Vermont Studio Center. He received a BFA in painting from the Massachusetts College of Art and Design and an MFA in sculpture from the University of Pennsylvania. He is based in Washington, District of Columbia.

Web: seanrileystudio.com

Instagram: @studioseanriley

Jean Seestadt is a multi-media artist whose work draws inspiration from the personal to the art historical, addressing the bittersweet reflections, stifled anger, and humor in everyday relationships and spaces. In her embroidered works, she documents the silent anger and indignities of institutional spaces, with each stitch repetitively tallying the time we spend there. Her work has been exhibited in the United States and Europe, and she has participated in residencies at Carter Burden and the Wassaic Project. She has been reviewed in several publications including The New York Times, Hyperallergic, and The Huffington Post. She received her BFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and her MFA from Hunter College. She is based in Brooklyn, New York.

Web: jeanseestadt.com

Instagram: @jeanseestadt