by Aaron Wilder, Curator of Collections and Exhibitions at the Roswell Museum

Roswell Daily Record

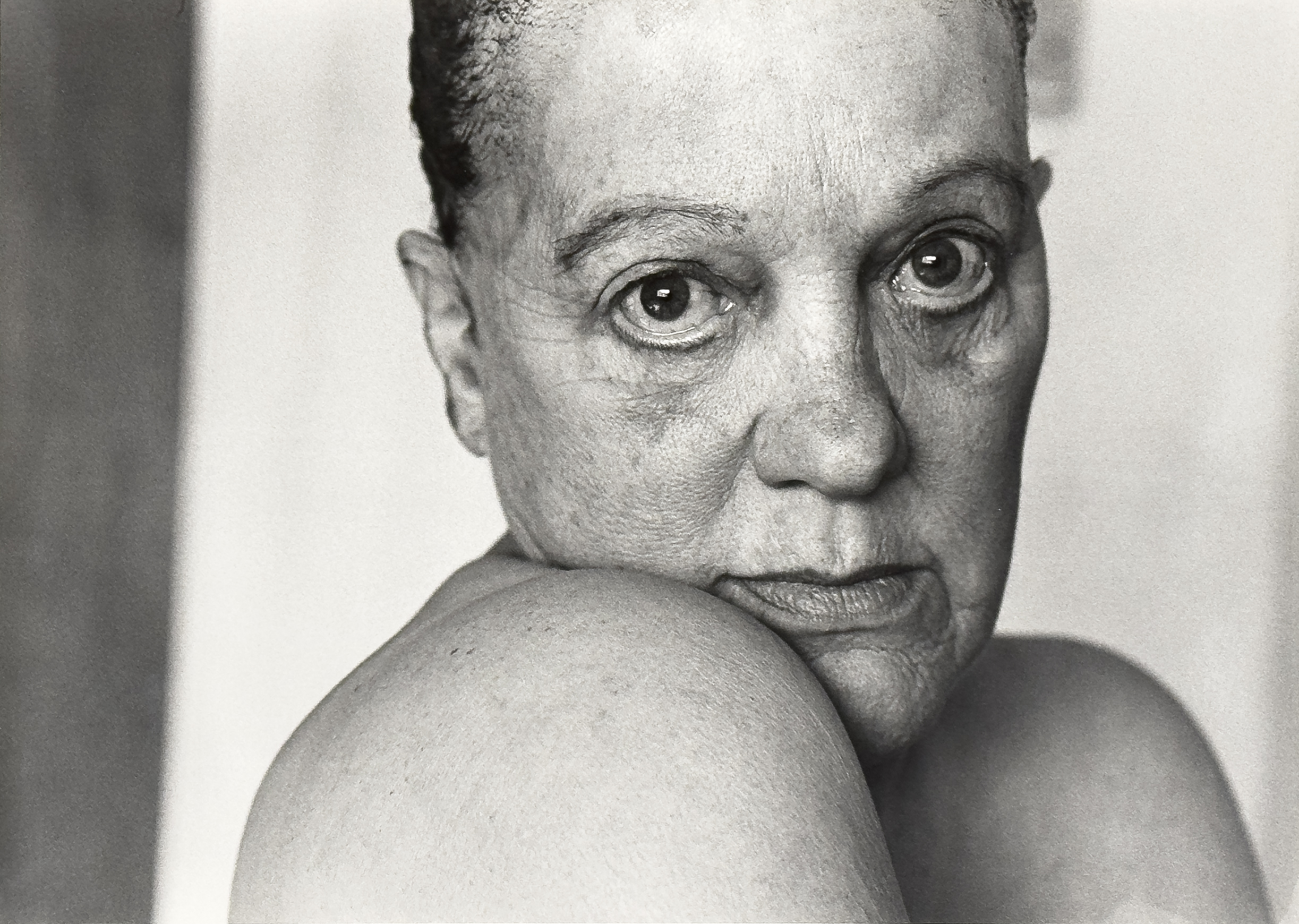

“A Rose is a Rose” by Anne Noggle, 1985, Silver Print, June Middleton Estate Fund Purchase, 1988.028.0002

As a pilot, photographer, curator, and poet, Anne Noggle defied convention. Often turning her camera on herself, she questioned society’s view of aging women. Lauren LaRocca included part of Noggle’s poem “Sketch for a self-portrait” in the Santa Fe New Mexican in 2019; part of which reads: “I have lost my way; And my face reminds me of that; Every Stop and Start, love and loss legible; A whole individual story and who will read it; Who will look at my face and find me there?”

Anne Noggle was born in 1922 in Evanston, Illinois, and raised by her mother, Agnes, after her father abandoned the family. Agnes supported Anne and her older sister, Mary, by placing them in a boarding house while she worked in a bookshop. As a teenager, after seeing Amelia Earhart fly at a Chicago-area airshow, Noggle asked her mother for permission to take flying lessons. She earned her pilot’s license in 1939 at age 17, during her senior year of high school. In a 1994 article for the Houston Center for Photography, K. Johnson Bowles quoted Noggle as saying, “women can do whatever they are bold enough to do.”

From 1943 to 1944, Noggle served as a Woman Air Force Service Pilot (WASP), a civilian corps created during World War II to free male pilots for combat. WASPs test-piloted aircraft and weapons systems, ferried planes, trained pilots, and carried out hazardous towing missions, often with minimal equipment. After the war, Noggle worked as a flight instructor and air show stunt pilot from 1945 to 1953. When the US Air Force later offered commissions to former WASPs, she applied and returned to service during the Korean War. By the time she was discharged in 1959, she had risen to the rank of captain and logged more than 6,000 flight hours. She retired early due to emphysema, which developed while she was crop dusting, and received a disability pension. For a 2016 exhibition at the New Mexico Museum of Art (NMMA), Noggle is quoted as saying “There is a resemblance, I think, between flying and photography. Both are done alone, in concept anyway, and both require independence and optimism, and some dumb courage.”

Following her retirement, Noggle moved to New Mexico, where her mother and sister lived, and used the GI Bill (a US federal government program providing benefits to those who served in the military to help them transition back to their daily lives) to pursue higher education. Johnson Bowles quoted Noggle as saying, “I was excited about the possibility of going back to school. At first, I decided to be an art historian. I attended the University of New Mexico [UNM] when I was 37. In my last semester Van Deren Coke came to the university as chairman of the art department and started the photography program. So I took a class in photography.” She earned an undergraduate degree in art and art history in 1966 and a graduate degree in art in 1969. Noggle taught at UNM from 1970 to 1996. Johnson Bowles quoted Noggle as saying, “Initially, I used a wide-angle lens to take in all I wanted around me which probably stems from my years as a pilot—scanning the horizon. Those were in my early photographs. It felt good to photograph that way. It took me a while to get closer to people, to really look at them as portraits.”

What Noggle would become well known for was portrait photography, particularly of older women. She began by photographing her mother and those of her mother’s generation. Johnson Bowles quoted Noggle as saying “I was both surprised and then shocked by the degree of discrimination directed against the elderly, and its de facto acceptance by the society at large. It became a cause for me and a dominant direction in my work—not pathos, certainly not wrinkles, but strength, and beauty and humor and the aging of human beings whose lives are so visible.” Noggle photographed women at very close range, often magnifying signs of aging. Reflecting on this, LaRocca asked, “Was she celebrating aging or is she simply documenting its brutal truth…?”

At age 48, Noggle had her first one-woman exhibition in 1970 at the One Loose Eye Gallery in Taos, New Mexico. During the same period, she volunteered at the NMMA, serving as its first curator of photography from 1970 to 1976. In 1977, decades after their wartime service, WASPs were officially recognized by the US military and granted veteran status. As Noggle herself grew older, she often turned the camera on herself, documenting her own aging. Art critic, writer, and curator Lucy Lippard wrote in 2019: Noggle “used herself ‘universally,’ exploring emotions by seeing herself as a catalyst for seeing others.” In the 2016 NMMA exhibition, it was written that her self-portraits “present many guises to the camera – some real, some imaginary – and connect her firmly with both the feminist artists of the 1970s and to a long line of contemporary female photographic self-portraiture.”

Noggle received National Endowment for the Arts grants in 1975, 1978, and 1988, and a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship in 1982. Over her lifetime, she exhibited widely throughout the United States and internationally, including shows in Europe, Canada, Japan, and Russia. She continued working in her darkroom until suffering a stroke in 2003, after which she turned to writing poetry. Anne Noggle died in her sleep in 2005 in Albuquerque. In her obituary, she’s quoted as saying, “I want to look as young as I feel inside.” Similarly, Elaine Woo quoted the artist in the Los Angeles Times in 2005 as saying, “I hope that all of my images have or hold in some sense the heroics of confronting life.”

In 1988, the Roswell Museum purchased two photographs by Noggle, including this 1985 print of A Rose is a Rose. Reflecting on posing for an Anne Noggle portrait, LaRocca quoted Betty Hahn, long-time friend of the artist (and a photographer herself), as saying, “I thought I’d look how I look. But when I saw the pictures, it was always something different from what I thought it would be. They were always a surprise to me… She was good at making people look the way she wanted them to look.” There are many origins of the phrase “people see what they want to see,” but this is referred to in modern psychology as confirmation bias. Whether conscious or not, Noggle saw in older women a beauty and strength and that is what she captured in her photographs. Johnson Bowles quoted Noggle as saying, “To look straight into a face and find a pulse of what it is to be human, that is what fuels me.”

The statement “It’s Your Art” is meant to emphasize that the Roswell Museum’s collection is your collection. Despite the museum’s closure due to the October 2024 flood, staff continue to work behind the scenes on care for and conservation of collection objects. Please stay tuned for more from the Roswell Museum. We appreciate the outpouring of support from the community during our closure. And remember, “It’s Your Art.”